An Interview with John Farnam

An Interview with John Farnam

Interview by Gila Hayes

Prominent firearms instructor and our Network Advisory Board member John Farnam advises armed citizens to resolve hesitation about killing in self defense before a violent criminal attack forces the issue. “You’ve heard of the ‘fight or flight’ response to deadly threats,” he notes. “What is far more likely is ‘freeze or panic,’ and in real, violent criminal attacks, we see both routinely, even among those who ostensibly know how to operate a gun, with predictably dreadful outcomes,” he writes in his DTI Quips at http://defense-training.com/2017/the-thick-of-the-fight/.

Pondering Farnam’s comments, I reflected that armed citizens get seemingly contradictory advice. Training emphasizes dire legal consequences for using deadly force. On the other hand, attacked with deadly intent, full commitment and ruthlessness is essential to saving innocent life. Both are vital. Encouraging armed citizens to resolve the issue of willingness raises accusations that armed citizens are irresponsible and bloodthirsty. As a result, many avoid confronting this sobering subject. Fortunately, John Farnam is not one to shy away from difficult topics, so when I asked if he would talk with us about killing to survive a deadly force attack, he graciously agreed. We switch now to Q&A to learn from Farnam in his own words.

eJournal: Thank you for agreeing to discuss acknowledging the harsh reality about killing in self defense. How do your students learn the ruthless determination needed to survive a violent criminal attack? Many find it very unnerving so they avoid the subject.

Farnam: This disinclination to face the reality of what is going on in front of us is endemic, especially in Western civilization. Most of us are not desperate, we have good things going on and we do not want those things disturbed. We don’t want our lives disturbed by even thinking about something that might disturb it!

As an instructor, I have got to compel students to confront the point I am trying to make. So, for instance, I don’t say, “If,” I say, “When.” The moment you say, “Do this if something happens,” that sounds theoretical and your student is going to think, “Well, that would never happen to me,” and they will dismiss that because it is convenient. You have fairly offered them the chance to wiggle right off the hook.

Replace “if” with “when” and you compel them to face the point you are trying to make. It makes your speech more powerful and effective but it also makes it less comfortable. We have to confront our students with, “When this happens…” not “This might happen,” so I say, “This will happen and you will endure the consequences.” When confronted with that, students become uncomfortable. I have had students tell me, “I don’t want to have to think about all these things that you talk about.”

eJournal: The problem is, you can’t encourage a false sense of security.

Farnam: To make training relevant, you have to tell students why they are taking the course. Students come to me often in a state of confusion. They’re at my course because they are frightened, but they don’t know what they are frightened of. They can’t or don’t want to articulate what scares them, so I say, “I can tell you why you are here. We are going to give you some ways of dealing with this that are more effective than what you have now, which is probably nothing.” Instructors have to help students confront why they came to class and a lot of that includes holding a mirror in front of their face, which is going to be less than pleasant.

eJournal: You make students confront fears about being killed or crippled and what is required to prevent it. Have you noticed how many instructors rely on cute slang like “Light him up,” instead of stating clearly, “You shoot him,” for example? Is slang another way we deny the reason for armed self defense?

Farnam: Yes, I think so. Tom Givens asks his students, “Why do you carry a gun? Why do you own a gun?” The answer from people who have not thought about this very thoroughly usually begins with an apology like, “Well, I really don’t want to hurt anybody, but…” Tom confronts them by responding, “Well, I carry a gun so I can shoot people.” Can we get that out in the open? It breaks the ice so people think, “Oh, I guess it is OK to talk about this now.”

We could talk about self defense very surgically or like we might talk about the price of corn, but at some point, we have to talk about the death and pain and suffering that we’re going to cause directly on another human being when presented with no other choice. That is what is so hard to get around! Is there any other way? Well, no, there is no other way left when all the other ways are precluded. Now, we have to face this directly. No doubt it is going to be awful, and it will probably be something you will think about for the rest of your life, but at least you will be alive to worry about it.

eJournal: I think one reason we avoid discussing that we carry guns to shoot violent attackers is because we’re scared we’ll be accused of shooting supposedly innocent people. That is a lie that encourages laws that further erode our rights to have guns to defend ourselves and our families.

Farnam: There is always a risk! You may be accused of being flip and casual when trying to talk frankly about killing. People may say, “You are being so uncaring in talking about this very serious subject.” No matter how you put it, those accusations are going to come your way.

The other choice is to avoid the subject altogether and to dance around it. The NRA is famous for that because they have their agenda, too. They don’t want to offend certain politicians whose support might be jeopardized. I understand their position, but like you, I have decided that my students’ interests have to come first. We can never compromise because we are afraid we might lose someone’s political support.

eJournal: It gets a lot more personal than worrying about politicians, too! Should we tell co-workers we spent our weekend receiving firearms instruction and deal with their prejudices and ugly jokes about gun owners?

Farnam: Well, if you make any preparations for any emergency, you run the risk of being accused of being a paranoid prepper. Those accusations always go with training. If it is a hurricane, a fire, a tornado or if it is something else, whatever precautions you take, from building a shelter to whatever you do, someone will say, “Oh, you are overreacting.” You have to be prepared for those kinds of accusations and understand that, well, I have to be firm in what I am doing, in spite of the fact that there will be people who won’t understand.

Is it possible to go overboard? Of course, it is, and that is where the term “reasonableness” comes in. We cannot prepare adequately for everything that could possibly happen. We have to make reasonable preparations, realizing that there is always more we can do. Yet, whatever we do probably won’t be adequate but it will be better than being caught flat footed.

There are a lot of people who find fault with getting a concealed carry permit and getting some training, who say, “Well, you’re just begging the question.” I often refer to George Patton’s famous quote, “No fire drill has ever caused a fire.” Fire drills don’t cause fires, but most of us feel fire drills are necessary so we aren’t doing it for the first time when there actually is a fire. But when we do fire drills, we don’t say, “Well, that causes me to think about fires, and that is very unpleasant. I don’t want to do fire drills.” Well, of course not, that is nonsense and completely false thinking, but that is not uncommon.

I’ve heard people argue that evil begets evil and if you don’t think about evil, then evil won’t come your way. We know that is nonsense, but there are a lot of people who believe that.

eJournal: Fire drills make a good example. Now, compare fire drills to exercises you do with your students. Someone attacks us with lethal force. Will we freeze in panic and die because we fail to get moving and reacting? Or are we going to tap into one of the several standard responses you teach? Most honest people admit that they wonder what they’ll do if attacked. What do you teach to avoid freezing in panic?

Farnam: A big part of our training is avoidance and disengagement. When someone is offering violence, we teach to aggressively disengage and separate.

eJournal: Instead of stopping to figure out what’s happening, you teach an immediate disengagement technique–the famous Farnam tape loop: “I’m sorry, sir, I can’t help you!” It gets us into action before a physical attack can start. Without having to judge, “This guy looks really dangerous, I’m scared,” we’re deciding, “People in general shouldn’t get that close to me,” and stop a risk before it develops.

Farnam: We’re saying, “I’m sorry, sir, I can’t help you,” with the knowledge that we are carrying our trump card. My trump card is right here [pats holstered pistol]. He can’t see it; he doesn’t know it, but I do. I know I have options. I know that if nothing I’m doing is adequate, I can always go to the next step. With that knowledge, I can be far more convincing. I can be far more successful with my less-than-lethal approach than someone who has nowhere to go when it doesn’t work.

Disengagement is a big part of our training, but we can’t give students the impression that it just ends there, that any lethal confrontation can be avoided and diffused. That is not true! We have to have the ultimate solution at hand and ready to go and then, with everything else in place, a lethal confrontation is only less likely, not impossible.

You do not get a risk-free life. Students come with the false expectation, asking, “Show me what to do. Show me if I adhere to what you tell me to do, that nothing bad will ever happen to me.” I can’t.

The only thing I can guarantee you is that in the end, the Valkyries will have their victory. Between then and now, I want to expose myself to every good thing this life has to offer. Part of growing up and maturing is developing the ability to distinguish what we call normal risk from suicidal risk or risk that has no benefit. When people take suicidal risks and are injured then say, “I had no idea! This was not fair,” I wonder, “What planet are you from? Are you six years old or something?!” This is something you should learn as an adult.

It applies to what we do with guns and when we take the same philosophy and apply it to everyday life, we don’t go to stupid places, we don’t associate with stupid people, we don’t do stupid things. Will that guarantee that nothing bad will happen to us? Of course not! It makes it less likely. In the end, despite your best efforts you may be confronted by a circumstance where you have no choice but to apply deadly force in a very ruthless and aggressive manner.

eJournal: What is your opinion of scenario-based training in which students literally rehearse force options up to and including having to shoot when it will keep them alive?

Farnam: The scenario training that we do is very helpful. I’ve had many students tell me after a scenario, “I had no idea I would do that.” It is a chance for people to experiment with behaviors that would be difficult to practice any other way.

I tell students, “Don’t do what you think I want to see you do!” I invite people to experiment with different ways of stopping threats and quit worrying about it not coming out right or having a bad outcome. In training, if something has a bad outcome, no one gets hurt and we all learn from it. Participating in those kinds of drills is immensely valuable and pretty hard to practice any other way.

eJournal: When working toward “owning” a skill, mental rehearsal and imagining each step toward the desired outcome is often recommended. Is that healthy where we are engraining self-defense responses?

Farnam: Sure! When you are out and about, play little “What If?” games. That is healthy as long as you don’t obsess on it. Ask yourself, “What would I do right now if…” Keep reminding yourself that disaster hovers over me continually and sometimes it is the arbitrary whim of chance that I find myself in a difficult situation. Don’t become overly suspicious, but ask yourself innocently now and then, “If this happened right now, what would I do?” I think that is healthy.

eJournal: Socialization teaches such aversion to hurting anyone to say nothing of killing, that I wonder how

armed citizens work through such powerful anti-self-defense programming. Some have suggested that hunting or killing animals for meat is a way to confront mistaken beliefs that all violence or killing is wrong. Do you debunk or endorse the suggestion that hunting helps resolve internal questions about killing?

Farnam: When we hunt, we approach an animal we just killed and see the blood and other consequences, and I think seeing the result of using our guns is a good thing. Although it is an animal and not a human being, having that experience is probably good. Whether that will make you more or less hesitant in a life or death circumstance, I am not enough of a psychiatrist to be able to give an opinion. I sure enjoy big game hunting and I’ve hunted dangerous game. I once shot a charging cape buffalo, and I’ve often said, “I really do not want to do that again!”

eJournal: Maybe so, but you came away with a better understanding of how you reacted with your life hanging in the balance.

Farnam: When I undertook that hunt, I knew what was possible. I’m a big boy; I knew what my decision meant. If someone said, “We’ve got a cape buffalo hunt and do you want to go?” I would probably say, “No, I’ve already done that.”

Now days, we hunt pigs and goats and such and as far as I know none of them are particularly dangerous, but they don’t give themselves up to us. We have to stalk and identify short windows of time in which to shoot and in the end, we have to approach this animal we just killed and see the consequences. I’ve shot something that was alive. I’ve shot things other than just paper targets and steel plates. If a student asked if they should take the opportunity to hunt, I would probably say, “You should probably take advantage of that opportunity.”

eJournal: What value, if any, do you find derives from asking students to envision loved ones for whom they would kill to prevent death or injury from violent attack?

Farnam: I know it is upsetting for people to think about their children and their family members being homicide or violent crime victims. It is difficult to think about. We don’t need to dwell on it, but like everything else, I think we have to talk about it frankly. You are not learning to shoot just to protect yourself, it is also to care for family members. Yes, ending someone else’s life is regrettable and we do not like doing it. We certainly try to avoid it, but when it is acutely and obviously necessary, I will never hesitate. I won’t hesitate a second to do what circumstances would dictate any reasonable person would do.

I don’t like to dwell on this stuff. I don’t like to be overly gory. I remember when I took driver’s education years ago, there was a film called “Signal 30” that showed a bunch of bloody car accidents. It struck me, although I was only 17 at the time, that they were really beating this to death! I said, “OK, I get it!”

I think in teaching self defense, while we don’t dwell on it, we do bring up criminal violence because we can never forget this is why we have guns. It is our solemn responsibility to protect our children and to protect other family members. That is a burden you voluntarily take upon yourself and you have to take it seriously.

eJournal: You’ve used the words “ruthlessness” and “aggressiveness” and I wonder if that mental state is active only if innocent life is threatened by another person?

Farnam: Perhaps we shouldn’t use the word “ruthless,” since it has a negative connotation. We tell students that it may come to a point where you have to act without hesitation. You can’t hesitate, you can no longer mull this over in your mind, you have to act quickly and with everything that you have.

As Machiavelli was famous for saying, “Never do your enemy a minor injury.” We are talking about the maximum use of force, and so is ruthless the right word? We might substitute some other words, but you know me well enough to know that I do not back off from making the point. I use powerful, connotative words to force you to confront the point I am trying to make instead of offering you a way to get off the hook.

eJournal: While I have no problem describing self defense as “ruthless” when innocent life is threatened, your description of acting with full commitment to stop the danger fills in the “how.” Do we make it clear that reacting ferociously is situational and that willingness to kill emerges only if we or those we love are threatened?

Farnam: That is exactly our refuge. This was not my choice; I did not want this. Apparently, the other person wanted this and left me with no choice. That is our

psychological refuge, because in the end, you say, “Look, this was not my choice. I did not go looking for this. In the end, I did what I had to do.” If there’s a way to rationalize it, that would be the main one.

eJournal: That puts violence in context. Now, moving beyond this great one-on-one discussion in which you’ve educated me, I wonder if we need to have these discussions more publicly? Armed citizens have to reach their own internal convictions and then need to help those in our immediate care understand what may be necessary to save them from harm. Next, there is the body politic. Coming to grips personally is hard enough! Do we need to go public?

Farnam: That is also difficult, particularly with minor children, who, depending on their age, are capable of understanding only so much. It is silly to have deep discussions with children who are not prepared to understand. With the very young, you have to be in charge and if you say to them, “Go there; do this,” they have to do it. The deep details are just going to have to wait until children are old enough. Let them be children for a while! I truly don’t want to try to confront a poor child who is not psychologically prepared to confront life and death with stuff that is unpleasant for adults.

eJournal: What about discussions with spouses?

Farnam: With adults, I think we have to confront this frankly. You need to say, “This is our procedure for every day. It affects the way we get into the car, the way we get out of the car and the way we walk and go about in public. Everything that we do is going to proceed from this discussion we are about to have.”

In this civilization, we have the bad habit of dancing around unpleasant issues. Too often, we substitute weasel words and phrases for strong, connotative language. This discussion needs to go beyond, “Let’s all be safe.” It has to go to, “You may be with me some day when I have to end someone’s life with this gun. It is time that we confront that now. Without dwelling on it, we have to think about it now, so when it happens, it doesn’t hit you in the face.”

eJournal: How much should we try to explain deadly force in self defense to the general public? Should we try to explain this to the pacifists who are passing our laws?

Farnam: [sighs] Yep. There is a good question. My students come to me because they want to be there, even if they have not yet articulated it clearly. At least for the philosophical part of it, most are clearly on their way. The great unwashed in society have never thought about killing, they probably never will because they don’t want to. I will probably never have nor want 99 percent of them as students.

eJournal: But some of that 99 percent are writing the laws that will affect you, me and our Network members. Should we try to justify shooting in self defense for that reason?

Farnam: In my Quips, I try to espouse our philosophy and help people understand the righteousness of what we are talking about. It is my small effort. When I am listening to the news and hear how amazingly naïve the people being interviewed and the commentators are, I just shake my head. I don’t know what we are coming to. For what little we can do, I try to influence the people I can, and not with the attitude that I have all the answers because we are all learning every day! I think that our philosophy and the way we express it can be helpful to a lot of people. When people want to be helped and they come to me, I am not going to turn them away.

eJournal: We have all benefitted from you addressing tough issues frankly and without giving us an out to retreat to a more comfortable world view.

Farnam: Those we teach may never forgive us because once we open Pandora’s box there is no going back. They were much more comfortable when it was closed. Well, that’s what we do.

eJournal: You speak the truth with boldness; we must reciprocally find the courage to listen to the truth. In the same way, armed citizens need the resolve to expose those in their circle to choices about self defense and the defense of those we care about, even when the discussion is not warmly received. Self-sufficiency is pretty unpopular!

Farnam: They have to move from childhood into adulthood. There is a lot to be said for childhood! A lot of us sometimes wish we could just stay children, but if you plan on dying of old age you had better grow up fast.

eJournal: That’s a great axiom! This hasn’t been an easy interview, so let me close by asking if there are topics and questions I’ve failed to bring up. What else do Network members need to know about mental preparation to use deadly force in self defense?

Farnam: We’ve pretty much covered it. We are all out there trying to spread the truth in our own way. We are wonderfully effective sometimes and all of us are frustratingly ineffective sometimes! We try our best in our own unique way to present this to our students and in some cases, we are going to be effective and, in some cases, we even save people’s lives, but in some cases, we are frustratingly ineffective. We wish we could be more effective, but that does not discourage us from going forward and working with the people we can be effective with.

eJournal: Thank you, John!

__________

About our source: John S. Farnam, president of Defense Training International, is one of the top firearms instructors in the world, having trained thousands of federal, state and local law enforcement personnel, as well as non-police, in the serious use of firearms with emphasis on fully understanding the physical, legal, psychological, and societal consequences of their actions or inactions. Learn more about him at http://defense-training.com.

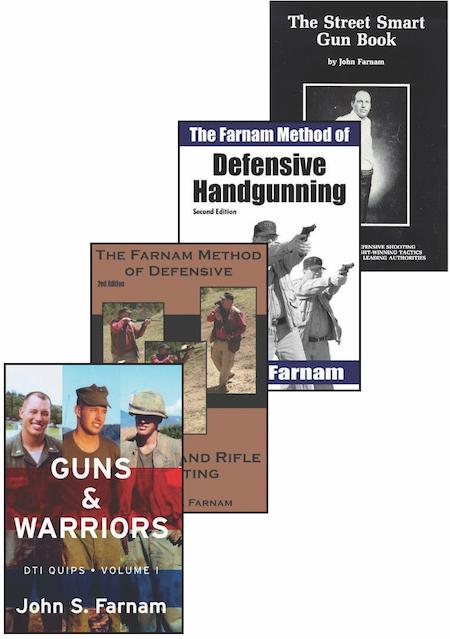

He is the author of four books on the subject–“The Farnam Method of Defensive Handgunning,” “The Farnam Method of Defensive Shotgun and Rifle Shooting,” “The Street Smart Gun Book,” and “Guns & Warriors – DTI Quips Volume 1.” John and his wife Vicki travel around the world teaching the latest concepts in defensive marksmanship and tactics. Courses are available for a variety of defensive weapons, plus Tactical Treatment of Gunshot Wounds.

To read more of this month's journal, please click here.