Including ... • Tueller Drill Revisited • President's Message • Beyond the Firing Line • A Tale of Five Witnesses 2 • Letters • Book Review • Editorial

Get eJournal PDF: click here

The Tueller Drill Revisited

by Gila Hayes

For readers unfamiliar with the name, Dennis Tueller retired with the rank of Lieutenant from the Salt Lake City, UT Police Department, taught at Thunder Ranch and International Training Consultants, the American Pistol Institute (Gunsite), Defense Training International, American Small Arms Academy, the U.S. Dept. of Energy’s training center, International Association of Law Enforcement Firearms Instructors and more. Currently he is with Glock Professional, Inc. as a firearms instructor teaching that company’s police firearms instructor and armorer courses.

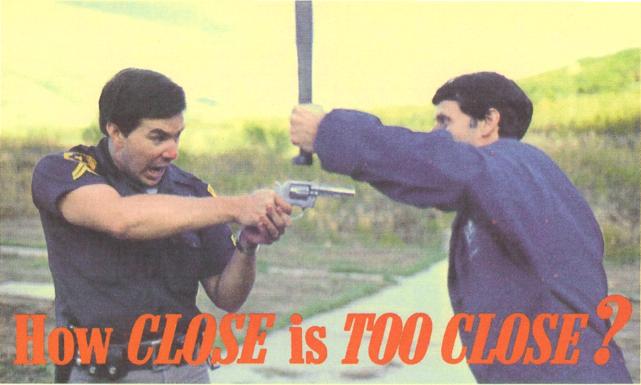

Dennis Tueller’s study went so far beyond him that his name has become inextricably linked with what is erroneously called the “21-Foot Rule,” as if an arbitrary distance could be established beyond which an assailant armed with a contact weapon was no longer an immediate threat, or put conversely, justifying use of deadly force if an assailant with a contact weapon was within a certain distance. (To read the original article, visit http://www.theppsc.org/ Staff_Views/Tueller/How.Close.htm)

In the year that marks the 25-year anniversary of Tueller’s original article, I thought it would be interesting to ask Dennis Tueller to revisit the topic, and see how his thoughts have changed over time.

eJournal: Dennis, 25 years ago you wrote an article sharing some conclusions drawn from a simple test you devised. Would you tell us about the history of what we have come to call the Tueller Drill?

Tueller: At the time, I was assigned to the Salt Lake City Police Academy, conducting firearms and other useof-force training. I was also teaching part time at Gunsite. During an academy training session, we had been doing draw-and-fire drills at the seven-yard line. During a break, we were discussing use of force issues and one of the recruit officers asked what to do if someone was attacking you with a knife, a club, or some kind of a contact weapon. He wanted to know how close an attacker should be allowed to encroach before the use of deadly force was justified to stop him.

Tueller: At the time, I was assigned to the Salt Lake City Police Academy, conducting firearms and other useof-force training. I was also teaching part time at Gunsite. During an academy training session, we had been doing draw-and-fire drills at the seven-yard line. During a break, we were discussing use of force issues and one of the recruit officers asked what to do if someone was attacking you with a knife, a club, or some kind of a contact weapon. He wanted to know how close an attacker should be allowed to encroach before the use of deadly force was justified to stop him.

At first, I thought about saying three or four steps, but then I realized that I didn’t have any idea how close was too close. I thought, “We can do better that this!” Since we already knew the average time it takes to draw, fire, and hit a target at seven yards – which was about 1 1/2 seconds from the holster – I decided to see just how long it would take someone to cover that same distance.

So we had one recruit officer play the role of the “bad guy” and another played the role of the “startled officer.” We put them 21 feet apart, and when the bad guy role player decided to start his attack, we started the stopwatch, and when the bad guy made contact with the good guy, we stopped the watch. I was quite stunned to discover that the time was roughly 1 1/2 seconds!

Then we tried the same exercise with everyone available in the class – some younger, some older, big and small, male and female – and all of them could run that seven yard distance in about 1 1/2 seconds. Of course, this was before Simunitions® or Airsoft®, but later we did test it with dart pistols. What we found was that if you’re ready and if everything goes perfectly, you might get the gun out and get a shot off before the bad guy role player makes contact. That is not good enough! Shooting does not stop the action.

So we started considering other things: seeing the danger so you had an early warning, getting the gun out, issuing a challenge, getting off the line of attack, and taking a big step back as you draw. At the time of the original tests, my thinking was not as broad-based as it is now. I was used to standing on the firing line and facing targets, planting my feet and shooting.

Later, I talked about the test with some folks at Gunsite, and they said “we have got to get the word out.” Chuck Taylor was the operations manager at Gunsite at the time, and also an editor for SWAT magazine. He encouraged me to write about it. In March of 1983, the article appeared in SWAT magazine entitled “How Close Is Too Close.”

EJournal: Have you any idea how your study morphed into the so-called “21-foot Rule?” Is that a concept to which you subscribe?

The term “21-foot Rule” was not one I used. In the article, I talked about recognizing the danger zone, and about using cover or at least obstacles to slow an attacker.

A little while later, people started contacting me about it. Manny Kapelsohn was working a case where they were defending a man who had shot an attacker who was coming at him with a crowbar. Then, I think it was later that same year, Massad Ayoob wrote an article addressing these same issues. And that’s where my name got attached to it. Massad Ayoob referred to this concept of reaction, response, time, and distance as the “Tueller Principle”, and dubbed the demonstration and training exercise as the “Tueller Drill.”

(Caliber Press (http://www.calibrepress.com/) referred to “How Close Is Too Close” in their second Street Survival book, “Tactical Edge” and used the terms “reactionary gap” and also coined the term “proxemics.” They later expanded on this in their excellent training video “Surviving Edged Weapons.” Then somewhere in the intervening years, the term “21-foot rule” crept into the lexicon. As Dave Smith at Calibre Press would say, that term was “a sticky idea:” a little concept that now, if you say 21-foot rule, most people in our field will know what you are talking about.

With that, I still think the “21-foot rule” is a poor use of terminology. Why not a call it a “rule”? Because words have meaning in the context in which we use them. What do you think of when you hear the word “rule?” “Follow the rules...” “Don’t break the rules...” “That is a violation of the rules...” In that context, the “21-Foot Rule” could be incorrectly interpreted to require you to shoot someone who is fifteen feet away and brandishing a knife. Conversely, it could be erroneously inferred that “the rule” prohibits the shooting of this same would-be slasher if he is twenty four feet and nine inches away. This may be over-stating the case, but I don’t think so, as I have heard people express both of these views when discussing the subject. For example, how long do you suppose you ought to wait if a guy is marching toward you swinging the legendary 32-inch blue steel machete? Are you going to wait for him to cross some imaginary line before you act to stop the attack? And what if there are multiple adversaries? How quickly can you effectively deal with more than one?

We also need to consider: Is it really 21 feet? Do you have an accurate tape measure in your eyeball to measure the distance? In addition to proximity, variables include the physical size and condition of both the aggressor and the defender, the presence of obstacles, cover, bystanders, partners, the terrain, footing, lighting, environment, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera. All of these factors combine to create the “totality of circumstances” which will drive our use-of-force decisions.

“Rule” has a nice catchy ring, but I think it is a very poor term. I would have never called it that. Your defensive tactics should be in response to whatever the circumstances dictate! What is your drawing time? With a high-security holster, an officer may take two seconds or more just to clear the holster.

Dr. Bill Lewinsky, a consultant at the Police Policy Studies Council (http://www.theppsc.org/Staff/ Lewinski/Bill.htm), has conducted extensive studies and elaborated on these concepts using high-speed photography and reaction response time testing. His is some of the best work in the business.

EJournal: Now, 25 years later, if you were re-writing “How Close is Too Close?” what, if anything, is different?

Tueller: How many times have we said, “If I knew back then what I know now?” I’d stress the concept of reaction and response. What I was trying to get across is that most people don’t realize how fast an adversary can cover the distance. I’ve seen this tested other ways, where instead of the adversary facing you, you have him on his knees, proned out or in a handcuffing position. Even then, it is surprising how fast some people can jump up and cover 21 feet.

EJournal: When you wrote it up “How Close is Too Close?” your article encouraged alertness; suggested withdrawing to a safer position; identified the “Danger Zone” of 21 feet and closer; moving to cover; suggested drawing the gun as soon as it is apparent danger is present; issuing a verbal challenge; and practicing the step back technique. We’ve talked about some of the other issues, what about the step back?

Tueller: When I was a new police officer in the 1970s if, during range training, someone had even proposed the idea of moving with a loaded gun in your hand, the Range Officer would have had you flogged! You planted your feet, toed the line and stayed right there. You loaded only on command and unloaded when you were done firing. It seems they were overly concerned with running a safe range, and thus were not doing a very good job of teaching officers how to win an armed confrontation. Me being a product of that type of training, I wanted to sell the idea of taking a single big step back as you draw - to gain a bit more distance from your attacker - as an acceptable technique. Of course I’ve come to realize that if one step back is good, six or eight are better if you can maintain control and move smoothly.

A lot of water has gone under the bridge since then and range training has improved. Renowned trainers like John Farnam and Clint Smith were among the first, in my experience, to have expanded on and popularized the concept of moving off of the line of attack as part of your response, although this is not as modern as we might think. You know the saying that there’s not much new under the sun? I was rereading my copy of “Fast and Fancy Revolver Shooting,” which was published in the 1930s. In it, Ed McGivern has pictures of how he taught officers in Montana during the 1930s to shoot on the move. At that time, he was probably considered a heretic! I’m sure most range officers thought that what he was doing was too dangerous.

So, the idea of moving and shooting is not brand new. Speaking only for myself, I think being able to move then shoot, shoot and then move again is tremendously important. So is moving when you see a potential threat, so you are not standing where the attack was directed. That way you can get inside your adversary’s reaction time, forcing him to react to what you are doing.

I have mixed feelings about shooting on the move. I know some people who have trained diligently, and who can shoot reasonably well while moving. For most of us, though, it probably is not a good idea to try shooting while you are moving. Moving, then shooting and getting some hits, then moving again, assessing and finding additional threats, that’s probably better.

EJournal: Finding additional threats? How do you train to overcome tunnel vision?

Tueller: Once you’ve engaged the threat, if it disappears, runs away or falls down, you need to get the gun out of your face, force yourself to breathe and move your head and eyes. The focal attention gets really intense when shooting, and that’s something we encourage by teaching that to get good hits you have to focus on the front sight. Because your vision is really tunneled in while shooting, you must recognize the tactical imperative to get gun out of your face when the shooting is over. It helps to physically move your head and upper torso. Like anything else, until you have trained to do it and built it into your routine, it won’t happen naturally. People have successfully used this method, and their feedback after confrontations is that they used it and that it worked, but you have to develop the habit before needing it.

EJournal: Most of our readers are private citizens who practice concealed carry. With the gun hidden under layers of clothing what precautions should be observed in the presence of possible attack with a contact weapon?

Tueller: That goes back to the issue of reaction and response time. The more time you need to physically access your defensive weapon and put it into action, then you need to have that much more distance that an adversary with a contact weapon would have to cover. The thing to do is to find out how long that is.

You could test this with a dummy gun and have a friend role play a bad guy to see how much distance would be covered before you could draw. Another variation I’ve seen on the Tueller Drill is done on a live fire range. The guy representing the attacker starts standing next to the shooter, but runs away from the shooter to the right, left or rear. When he pushes off from the shooter, the shooter draws and engages a target down range. The role player will drop a hat or some object when he hears the first shot. That marks the distance he covered before the first shot. This is something you can do very safely. And please remember: just firing a shot does not mean that the fight is over.

EJournal: So you mean that the slower drawing speed, requires longer distance awareness?

Tueller: No defensive weapon or plan is good enough if we are not alert enough to recognize that we have a problem. I teach this as the four “As” – aware, alert, act, and alive. This applies to everything—daily life, driving, and to a self-defense situation.

“Aware” means you recognize, believe, accept and understand that there are various kinds of dangers in daily life, and that – yes – it really can happen to you. If this is your mind-set, it is easier to remain properly alert.

“Alert” means that you are attentive to your environment, so your physical senses and intuition are turned on and tuned in. Jeff Cooper listed alertness as the first principle of personal defense (Ed. Note: See Cooper’s book Principles of Personal Defense http://www.paladinpress.com/detail.aspx?ID=1308). When you believe it can happen to you, your brain is geared to look for things that don’t look right; then you can avoid them. In the book “The Gift of Fear” by Gavin DeBecker (https: //www.gavindebecker.com/books-gof.cfm), he writes that to “fear less,” you should trust your feelings.

Then “Act.” Take appropriate action based on indicators your brain picks up, often at the subliminal level. Even though our modern, civilized conscious mind isn’t always able to recognize what the threat is. Being prepared to act can be based on “crisis rehearsal”. Do some mental imaging, do some training, visualize and mentally see yourself defending yourself, successfully surviving and prevailing. No one knows exactly what we may do, but if we have trained, we have a pretty good idea of our responses. We will respond as we have trained. Act on the threat indicators, and you can remain alive.

And that’s the final “A” – Alive. This is not all doom and gloom. There is more to being alive than just avoiding threats and danger. Yes it’s often a dangerous world, but if you are paying attention to your surroundings - not just walking around looking at the cracks in the sidewalk - you will also be more aware of the beauty all around. You’ll see the flowers, the sunshine, the kids playing, because you’re not focused on yourself and your problems. Keep your head and eyes up and pay attention, and enjoy.

EJournal: Your original article mentioned issuing verbal commands, and a lot of people carry alternative defenses like pepper spray. What about the time it takes to review our options and decide which to use? How could the human brain make a choice quickly enough before that second-and-a-half are consumed?

Tueller: You will see slower response times with a greater number of choices. With more options, comes more information you have to process. This is a two edged sword. Sometimes, less-lethal options, or distractions like pepper spray, have their place. But it does complicate the overall problem. Be familiar with whatever tools are in your took kit, and know how and when to apply them.

Thirty years ago, when I was a young cop, we carried a pistol and a baton. Those were your options. Now we have pepper spray, Tasers, strobing flashlights, etc. It can be kind of like choosing the between needlenose pliers or channel lock pliers, or using a socket wrench or a pipe wrench for a certain kind of job. Having lots of tools can be a good thing, but still, the more choices you have to make, the more time it takes brain to process and act on the decision.

EJournal: Does that mean instructors should advise against using some defense tools or tactics?

As instructors we shouldn’t presume to tell people what to do in every situation. What I can tell students is what I’ve learned from experience, and from research and study. But I can’t tell you if you should always fight back, since in some circumstances it may not be the best option. It is true that most studies of armed assault show that fighting back works more often than it fails, but I still can’t tell you what you should do in any specific situation. You need to believe it can happen to you. You need to recognize dangers in your vicinity, trust your feelings, and act based on your knowledge, experience and training.

eJournal: Thank you, Dennis, for sharing your knowledge and experience with us.

Ed. Note: Dennis Tueller recently agreed to lend his expertise to the Armed Citizens’ Legal Defense Foundation Advisory Board, for which we are very grateful. In this role, he will join other advisory board members in reviewing requests for financial assistance with legal costs from members who are being wrongfully charged after a lawful act of self defense.

President's Message

Attorneys Wanted!

Attorneys Wanted!

Things are going smoothly for the Network, and pieces are starting to fall into place. We have begun production of the DVD series we will send out to our members. Also at this time, we are starting to put together our list of Network Affiliated Attorneys. These professionals can help our members in the event they are wrongfully accused of a crime involving an act of self-defense. Consequently, I want to use my column this month to outline this very critical component of the Network, in hopes of making sure everyone is clear as to how this facet of the Network functions.

Already, I have put out at least two Internet flames this last month, where people thought the Armed Citizens’ Legal Defense Network, LLC was an attorney referral service. I don’t have a clue as to how people came to think this, but regardless, let me explain in very simple terms, that the Network IS NOT an attorney referral service. In fact, if a person who is not a member of the Network finds us and calls asking for a referral to an attorney who can handle a problem, we will not supply that information. This is NOT what we are all about, and the quicker people realize this, the better.

What we are starting to develop is a list of attorneys who are also NETWORK MEMBERS, receiving full member benefits, who also agree to be listed as a resource for Network members only. The lawyers pay us no fee to be listed as a Network Affiliated Attorney, and the Network receives no benefit, kickback or even free legal advice from the participation of these professionals in this aspect of the Network.

This great country of ours is home to thousands of attorneys who also share with us this philosophy: we are a nation of armed citizens who take it upon themselves to protect themselves and their families. It is these attorneys who we seek out, asking them to join the Network and agree to help their fellow armed citizen, in their local community, in the event the armed citizen needs their help.

In addition, the attorney affiliate does not need to be a criminal defense attorney, although that certainly is a plus if a case ends up getting litigated. The attorney that we seek should first and foremost passionately believe in the right to armed self-defense. He or she should be willing to get out of bed at 3:00 a.m. to go represent a fellow armed citizen who needs their help. They should also be willing to do a little study and educate themselves (with Network help, of course) as to the best way to represent a client who has just killed in self-defense. Network affiliated attorneys should be willing to do a little legal research beforehand on their own jurisdiction’s case law regarding armed self-defense, along with understanding the statutory constraints placed upon armed citizens using deadly force in self defense. Of course, neither the Network nor the Member should expect the attorney to give his or her services away, as no one should expect free legal advice.

In addition, in the rare event a member is charged and needs a criminal defense, the attorney should be willing to co-counsel with a specialist in the field, or simply refer the case out, if he or she is not a defense attorney.

With the above in mind, do you know of or are you the type of attorney we need to make this endeavor a success? Do you know of an attorney who belongs to your local gun club, or who is active in second amendment issues? If so, please have them contact me at mhayes@armedcitizens network.org and we will start the ball rolling.

On to other matters…

I am excited to report to you that our membership rolls have exceeded 200 members, which ain’t too shabby for an organization that is only three months old! Obviously, the idea we came up with a couple of years ago has some real merit, and we are more enthusiastic than ever, especially given the number of instructors who have signed up as members and who are spreading the word about us.

But, we need your help too. The quickest way for the Network to grow and become a powerful force in the industry is if each member spreads the word, too. We don’t want the Network to be a well-guarded secret, but instead, the name of our Network should roll off the lips of armed citizens everywhere. If each Network member shared what we have to offer with three other armed citizens in the coming month, our size would likely double in that month! Please let us help you help us.

One of our members recently printed 15,000 Network brochures for us, and we would love to send you some to distribute at your local gun shop, gun club or shooting event. These brochures don’t do us any good sitting in our storeroom; we need to get them in the hands of armed citizens nationwide. If you want us to send you some, please e-mail Gila Hayes, at ghayes@armedcitizensne twork.org and she will send them out to you. Marty

Beyond the Firing Line: Force on Force Training

by Karl Rehn

“What is force on force training and why do I need it? I have a gun and I’m pretty good at shooting targets.” I get asked some variation on this question all the time. The answer is that force on force training (FoF) develops essential skills that can’t be learned through live fire practice. “But I shoot IDPA every month and have taken Advanced Handgun from my local firearms training school. Isn’t that reality-based training?”

“What is force on force training and why do I need it? I have a gun and I’m pretty good at shooting targets.” I get asked some variation on this question all the time. The answer is that force on force training (FoF) develops essential skills that can’t be learned through live fire practice. “But I shoot IDPA every month and have taken Advanced Handgun from my local firearms training school. Isn’t that reality-based training?”

Consider the differences between real situations and the typical defensive handgun course of fire. The goal in a real situation is to avoid fighting if possible, by detecting the potential threat early and avoiding it through non-violent actions like leaving the scene, increasing your distance, changing your body language and expression, or communication. In a live fire training drill, the goal is to shoot the target(s) as quickly as possible. On the range, the “go” signal is usually audible (whistle, buzzer, someone yelling “gun!”), but on the street the “go” signal is most likely to be visual (see a weapon or hands reaching for a weapon). On the range, if you are too slow, miss or fail to use cover, the worst that can happen is a lower score. In a real fight these same errors can get you hurt or killed. On the range, targets are usually 2D, typically stationary and neatly placed to face you square on, within a narrow range of angles that keeps your projectiles in the backstop. On the street, the world is 360 degrees and threats are likely to be moving and oriented at any angle from square on to sideways. On the range, when the shooting stops the drill is over. In a real fight, after the shooting stops there may be first aid to render (to yourself or others), bystanders to interact with, and attackers still present who have stopped attacking but still must be controlled without violence. High stress shooting practice is good training but it simply does not include many elements that will be present in a real incident. Force on force training can provide this higher level of realism.

There are several types of force on force training. The simplest is role-playing exercises conducted with non-firing guns, anything from a pointed finger to a training replica (“red gun”). This training can be conducted in any facility since no projectiles will be fired, and no special safety gear is needed. In this mode, the “what if” game can be played against human opponents in a realistic setting, with the actual floor plan and obstacles that would be present. Gun-mounted lasers can be used in this type of training to provide feedback about where bullets would hit. This training can be done in your own home to work through a complete scenario, including all family members. Even those that are unarmed and are not involved in the fighting part can participate in force on force training and practice their actions.

The next level of force on force training uses low velocity training projectiles like paintballs, Airsoft BBs, or special equipment such as Code Eagle, AirMunition or Simunition. This training requires special safety gear and facilities and should be supervised by a certified instructor to minimize the risk of injury to all participants. Full face, neck, throat and groin protection are important. Engaging in this type of training wearing only “shop goggles” or safety glasses leaves many sensitive body parts open to serious injury. Using this equipment, real incidents can be simulated from slow speed up to real time, giving participants important experience and training. The highest level of FoF training is fully integrated, where physical contact is allowed in addition to training projectiles. This training requires the most safety gear and poses the greatest risk of injury, but provides the greatest realism.

Those that do best in FoF training pay attention to what others do and say, and are willing to act quickly in response. Action can be anything from simply moving away, making eye contact and communicating to more aggressive behaviors. Being able to think on your feet is essential, because anything can happen. In one of our classes we ran a convenience store scenario involving 6 students. One student played the role of the clerk with poor English skills. The others were given other roles: armed citizen, robber, unarmed customers. Each was sent into the store to shop or to wait for a good time to rob the clerk. My clerk opted to play his role by using only Spanish, and all of the customers, without being directed to do so, attempted to communicate with the clerk in Spanish also. I teach in Texas, where almost everyone knows how to order a beer and ask where the bathrooms are in Spanish. Even the robber attempted to tell the clerk to give him the money in Spanish. Conducting bilingual training was not the goal of the scenario and it wasn’t part of the instructions – but because the students were paying attention and adapting to what was happening around them, that’s the way the scenario evolved. This particular group of students was above average in their performance in all aspects of the scenarios and I believe that their awareness and ability to ‘wing it’ were the keys.

Ultimately your best odds for success in a crisis will come from staying calm and doing what you’ve been trained to do. There’s a gap between being able to talk through what you would do in a classroom setting and doing it (at slow speed or real time) in a simulation. What most people find is that the first time they participate in an FoF scenario, they make mistakes, but that their panic level and ability to use their skills improves as they get more comfortable functioning “in the moment” of the FoF training. Without the FoF training, they’d be making the mistakes they made in the training scenario during an actual incident, where the consequences are greater. The bottom line is that live fire training simply isn’t enough by itself to fully prepare someone to handle a self-defense situation. Thanks to the efforts of many instructors all over the U.S. force on force is available at many schools, and those that want to explore this training on their own can now find instructional books and DVDs and training equipment for sale.

About the author: Karl Rehn is the owner of KR Training (www.krtraining.com), a central Texas based firearms school. Their program focuses on skills important to armed citizens: firearms skills, unarmed skills and tactical skills learned through a mix of live fire and force on force training. In addition to teaching for KR Training, Karl works for TEEX (part of Texas A&M) managing instructors and curriculum for homeland security training on a nationwide Dept. of Homeland Security program.

A Tale of Five Witnesses Part 2

Note: in last month’s eJournal, the author described the legal challenges faced by a man who resisted physically after he was forcefully detained at a Wal Mart store. His case provides the chance to study how the legal system can work against the citizen in a case where that citizen elects not to allow non-law enforcement personnel to arrest him without cause. If you missed last month’s installment, you can download the April eJournal by clicking on the link to that issue and go to page 8 to get caught up with our story.

by Marty Hayes, J.D.

As I write this, the defendant in the case discussed last month is awaiting sentencing. After deliberating for a little over two hours, the jury decided that he was guilty of 4th degree assault, a misdemeanor here in Washington State. He should have been sentenced by the time of this writing, but his case was fraught with legal hassles and delays from the git-go, and wrapping it up has not proven any easier.

Why was the guy convicted to begin with? In my opinion, there were three reasons for the conviction. First: the greeter created a very sympathetic response, and the jury felt sorry for him. It is always bad when the jury feels sorry for your opponent in a trial. The second reason: the judge erred in not allowing expert witness testimony to clear up some issues of the case (as mentioned in part one). And the third reason: the jury likely did feel that the defendant used excessive force when he pushed the greeter.

So, how did the defendant come to be charged with a serious felony, punishable by several years in prison, for what I view as justifiable use of force in self defense? It turns out, the original charge WAS misdemeanor assault, but when the prosecutor viewed the store’s videotape of the incident, he felt the defendant pushed too hard, so decided to charge a felony. I should mention that the prosecutor was newly elected, and had little criminal prosecution experience. In addition, the greeter stated that the fall to the ground hurt his back, and he had to go into surgery and have his back fixed. This sounds pretty bad, until you look at the fact that the back injury was pre-existing, and this man was, in fact, scheduled for back surgery before the incident. But, even when the prosecutor’s office found out about this detail, they refused to drop the charges. Instead, the greeter all of a sudden began reporting that he had a knee injury, and they started to hang their hat on that damage.

What made the state’s felony assault case unravel?

The neurosurgeon who operated on the greeter testified that he felt the push and fall COULD have exacerbated the injury, but he could not say that it DID cause further damage. It was also discovered that the neurosurgeon withheld medical records that had been subpoenaed by the defendant, and thus, he was basically unbelievable at trial. He came across as arrogant, and was very evasive under cross-examination. In other words, there was no evidence that the push and fall did in fact exacerbate the injury, except for the greeter’s testimony that he was in more pain after the fall. But, we also observed that he, while being a sympathetic witness and figure, did not acquit himself very well on the stand, either. Of course, the other eyewitnesses’ conflicting accounts did not help the state’s case any, but it was the neurosurgeon who did the most damage. There were also independent doctor reports that contradicted the neurosurgeon’s analysis of the injury and necessity of surgery, as well.

All along, the defense’s problem was that the defendant was the one and only person who could literally save himself from being convicted, and he almost pulled it off. If he had been able to be his own expert witness, I believe he would not be facing sentencing for misdemeanor assault at this time.

How can someone be his or her own expert witness? Well, readers, that is the point of this whole story. You can be your own expert, if you know and understand the dynamics of violent encounters, and you knew that information before the incident. The best way I know to learn these details is to buy the video, “Physio-Psychological Aspects of Violent Encounters” from Police Bookshelf. It was produced by Massad Ayoob (one of our advisory board members), and addresses many aspects of violent encounters. Additionally, you should seek out additional training in recognizing and dealing with pre-assaultive cues. Perhaps the readers can suggest training venues that cover this important aspect of the discipline.

Lastly, I hope this tale has helped people understand the frailties of our criminal justice system. I see comments all the time on Internet chat boards, which state that as long as your shooting is justified, you don’t have anything to worry about. This is flat wrong, folks, and you would be well served to start putting together your defense long before you have to pull the trigger.

Letters, We Love to Get Letters!

To the Editor:

Last month John Farnam wrote a wonderful article on the history and importance of our Second Amendment rights, “How We Got Where We Are.” I thoroughly enjoyed his perspectives, as always. They also stimulated thoughts that I would like to address.

I have often found myself disturbed by the language used within the gun rights movement to describe liberals, their thought processes and their goals. The Second Amendment is a non-partisan issue. It is a right given to all citizens, to protect us and our nation.

Since the birth of our nation armed civilians have represented a wide spectrum of political views. In recent years, even more people who are politically liberal have seen the wisdom of maintaining and exercising their Second Amendment Rights. Now, more than ever, it is incorrect to use the words “liberal” and “anti-gun” as interchangeable terms. We must welcome, not repel, any responsible gun owner who is willing to fight with us.

We should also recognize that there are conservative politicians who have compromised our individual liberties in the name of safety. For example, in January 2008, Paul D. Clement, the U.S. Solicitor General under George W. Bush, filed a brief in support of the DC gun ban. According to http://www.worldnetdaily.com/index.php?fa=PAG E.view&pageId=45526 “Paul Helmke, of the pro-gun control Brady Campaign to Prevent Handgun Violence, told the (Los Angeles) Times he salutes the administration for its position.” That is really creepy!

I would like to leave you with this thought. While our focus as gun owners is mainly on the Second Amendment, we must be careful not to lose sight of the rest of our rights. No matter how noble the pretext, we cannot allow any politician, conservative or liberal, to destroy any part of our Bill of Rights. Robert Léger, Network member #139

John Farnam responds:

Dear Sir:

You’re right! Sometimes, I neglect to acknowledge that there are many pro-gun Democrats, even Liberals, who need not be arbitrarily excluded from our Fraternity. We need to convert everyone we can. Thanks for reminding me!

When two men agree on everything, one of them is unnecessary!

/John S Farnam, DTI and Network member #129

To the Editor:

Very impressive eJournal. Well written articles, professional in appearance, no inflammatory pro-gun rhetoric bashing another point of view.

Congratulations, Gila and Marty (and the others involved) on a well done product.

Gary LeClair, Network member #28

Book Review

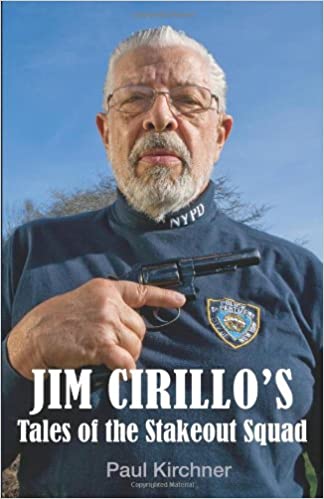

Jim Cirillo’s Tales of the Stakeout Squad

Jim Cirillo’s Tales of the Stakeout Squad

By Paul Kirchner 188 pages, including photo section

ISBN 978-1-58160-619-2 $25.00

When someone close dies unexpectedly, a few months pass and it seems you are doing fine…until something comes along to awaken the memories of the one you lost. That was my feeling when Paul Kirchner’s biography of Jim Cirillo arrived in the mail a few weeks ago. Part of me wanted to put it away on a high shelf and read it when I felt more stable. Another part was eager to open the cover and dive into the memories of knowing Jim.

The latter option won, and what a bitter sweet treat it was! At one point, I told my husband that reading this book was so much like talking to Jim that I just about couldn’t handle it. Still, it is to Mr. Kirchner’s credit that the stories ring so true, and the voice telling those tales is so clearly that of Jim Cirillo, Sr.

Kirchner explains that in preparing to write volume two of his popular book, “The Deadliest Men,” he undertook a chapter on Jim Cirillo. Before long, the author realized that the chapter on Jim would eclipse all the rest, and that trimming it to a reasonable length would excise many of the great tales for which Jim was so beloved.

“He (Jim) mentioned that Paladin Press had repeatedly asked him to write a book about his experiences with the Stakeout Unit (SOU) but that he couldn’t do it; writing was too much of an effort for him. I couldn’t understand this. ‘Jim,’ I said, ‘these stores are perfect the way you tell them. Just write the words down,’” the author explains.

During his interviews with Jim, Kirchner began to understand that Jim was unlikely to commit his memories to paper. “He didn’t do it, so I did. It would be a shame if the experiences of Jim Cirillo were lost,” writes Kirchner in the preface to his book. Then, on July 12, 2007, while Kirchner was right in the middle of writing about him, Jim was killed in an automobile accident.

The biography begins, appropriately enough with Jim’s early years, a Depression-era baby. Information shared is drawn, not only from Jim, but also from family members, fellow police officers, and others to whom Kirchner spoke. Though acquainted with Jim and his son, I was interested to see Jim through the eyes of his older sister, his daughter, grandchildren, and people with whom him worked.

But most of all, the author presents Jim Cirillo through the stories of Jim Cirillo. The language, the syntax, the expressions, the famous names…it’s all there: even the goat story, the tale of the “deadly druggist,” and Jim’s other stories.

Police training in the 60s and 70s was different. Cirillo’s stories of training NYPD’s officers recalls when cops primarily carried revolvers. As the book introduces the formation of the new Stakeout Unit and how they trained, we glimpse the genesis of the wonderfully intuitive trainer Jim would become. Jim told Kirchner, “Sometimes the faster we pushed them (trainees), the better they did, because they relied on the subconscious. The subconscious can do things so accurately and so fast, that no conscious thought can compete with it. The subconscious is so automatic, and it’s infallible once you teach the person how to do the thing.” Fully developed, these concepts would influence students who studied with him after his retirement.

Also hinted at is Jim’s life-long interest in ammunition design. In the book, we learn that his partner and fellow Stakeout Unit officer, Bill Allard, shared that passion. The author quotes another NYPD officer who details some of their reloading experiments. “When Jimmy was on the line at the range shooting with everyone else, you’d hear bang, bang, bang, BOOM! The range officer would come running over and then say, “Ah, you goddamn stakeout guys.”

The two became known at the morgue as “the two ghouls,” owing to their interest in autopsies of criminals shot with ammunition they had designed and loaded. Among their innovations was inverting the common wadcutter bullets to take advantage of a cavity at the base of the bullet, using this as the frontal surface. In addition, Cirillo carried the high performance ammunition of the day, Super Vel, in some of his guns.

In reviewing the operations of the Stakeout Squad, Kirchner includes the voices of other NYPD veterans who served with Jim. Despite public suggestions that the PD had loosed a band of killers on the city, these interviews emphasize the constraint, care and forethought put into setting up the safest possible fields of fire, as well as other operating procedures. The author corroborates reports of various stakeouts, bringing in details from other officers, to both flesh out as well as offer a different perspective on events. Kirchner carefully notes when the accounts deviate, and he references news reports of the time, as well.

In addition to stories of stakeouts, Kirchner relates Jim’s insights about on stopping power: thoughts from the man who’d seen up close when people were shot with a variety of calibers. Additional points include the speed with which these encounters took place, and the tactics and methods used by the Stakeout Unit officers, working in heavily populated environments. The author shares how Jim dealt with corrupt police officers, and how the department administrators and supervisors so often failed the men on the job. This is an insider’s look at a big-city police department in the ‘60s and ‘70s. It is no mystery why the Stakeout Unit was disbanded, but Kirchner’s interviews with the men who served alongside Jim provide viewpoints we are not likely to find elsewhere.

I just finished rereading “Jim Cirillo’s Tales of the Stakeout Unit,” and it’s hard to write a conclusion that isn’t maudlin. All I’ll say is buy this book. It is heart warming, heart-wrenchingly real, and you will enjoy every word, whether you knew Jim personally, by reputation or are only now hearing of him. The lessons taught by Jim Cirillo, Sr. live on beyond him, thanks in large part to Paul Kirchner’s excellent work.

Paladin Press Gunbarrel Tech Center 7077 Winchester Circle Boulder, CO 80301 303-443-7250

Shooting Back: The Right and Duty of Self-Defense

By Charl Van Wyk World Ahead Publishing,

2463 W 208th St., Ste 201,

Torrance, CA 90501

310-961-4170,

www.worldahead.com

ISBN: 978-0-0-97-904511-0 $14.99

Religion, self preservation, firearms, societal responsibilities and faith, make a challenging synthesis for Christians. All too often gun owners and self-defense practitioners are called on to answer challenges from family members or acquaintances who propose that from their Christian viewpoint, using deadly force defensively is either wrong, or demonstrates a lack of faith.

Because faith and belief are such personal matters, arguing the point is often counter productive. Instead, if asked those questions by someone who is quite devout, I recommend pointing them to a small book written by Charl Van Wyk, the man who shot back when terrorists attacked the congregation at his church.

Van Wyk’s account of the 1993 incident and the aftershocks that followed is fascinating purely from a biographical viewpoint. In addition, the author spells out how he came to his strong conviction that Christians have a responsibility to defend themselves and their family, as well as bringing in arguments from others who influenced his thinking. The book outlines Van Wyk’s rather strong religious beliefs on additional topics, and if the theology does not match your own views, try to keep an open mind so it doesn’t over shadow the rest of the message.

At just 91 pages, “Shooting Back” doesn’t require long to read and is well worth the time it does take.

Editor's Notebook

The Danger of Dogma

The Danger of Dogma

“I just don’t know what to do! First, I took training at my local gun range, but I wanted to learn more. When I went to another instructor, he told me that much of what I had learned was wrong and said that I had to change. I feel like I wasted my time!” exclaims the voice coming through my phone.

“Were the second instructor’s corrections about safety?” I ask.

“No, he got on me about how I was standing and how I held and pointed the gun,” she replies indignantly. “I’m afraid if I go to another shooting school, I’ll have to relearn yet another way to do this stuff. What a waste of time!”

The One True Way

Shooting schools differ little from any other discipline that brings people together for education and training. Favored methods and techniques all too easily become doctrine (defined as a body of ideas taught as truthful or correct), and in our zeal to impress upon our students effective ways to shoot, instructors often give the impression that their preferred method is “the one true way!”

The student, having invested substantial money and time, usually falls in line, essentially becoming the instructor’s disciple. All too often, this devotion short-circuits receptiveness to learning additional shooting methods, sometimes to the extent that the student may not learn crucial skills or grasp vital concepts they will need if a real-life self-defense emergency imposes on them circumstances the instructor has not considered or experienced.

Even if the instructor touts “been there, done that” life experience, who is to say his or her circumstances will be mirrored in a situation in which the student needs their firearm to save a life? Solving this quandary is not as easy – for either the student or for the instructor – as casual thought suggests!

Choosing which techniques are right for your circumstances is no easy chore. Police officers are tempted to simply accept without question the doctrine taught in the 80 to 100 hours of firearms training in basic law enforcement academy, and too many officers go through their initial training, yearly in-service training and qualifications without questioning the techniques they are taught.

Likewise, when the private citizen seeks out training, the techniques espoused in a $400 defensive handgun class taught by a charismatic instructor are difficult to abandon. Other times, the instructor carries an impressive pedigree of national, regional or state shooting match championship titles, to which the humble student’s experience cannot hold a candle.

Finding Your Own Way

But what if some of those techniques and tactics don’t fit your circumstances? The stakes are greater than a tongue lashing from a commanding officer or an admired instructor – in the worst case, using an unsuitable tactic or shooting method could cost a life.

The time comes when you must decide what fits you best, preferably before a self-defense emergency renders the need for those skills very real and exceedingly immediate. Learn and gather as many techniques as you can; then, when your “bowl” of knowledge is full enough, pick out what applies to your circumstances. Training from a variety of sources is essential, because the bowl method won’t work if you’ve mastered only one or two techniques!

Blindly adopting the style of a single instructor is unlikely to provide your best defensive handgun technique unless you are an exact clone of the man or woman from whom you receive instruction! Get out there and learn as much as you can, then and only then, can you select and perfect the techniques you may need to use in a self-defense emergency.

And the lady who called and got me thinking about all this? She’s off to Alabama for instruction from a well-known instructor, and she’s considering participating in Lethal Force Institute’s first level class with her husband when it is offered in their home state. She’s well on her way to synthesizing knowledge from a variety of sources and will eventually be ready to formulate her own way.