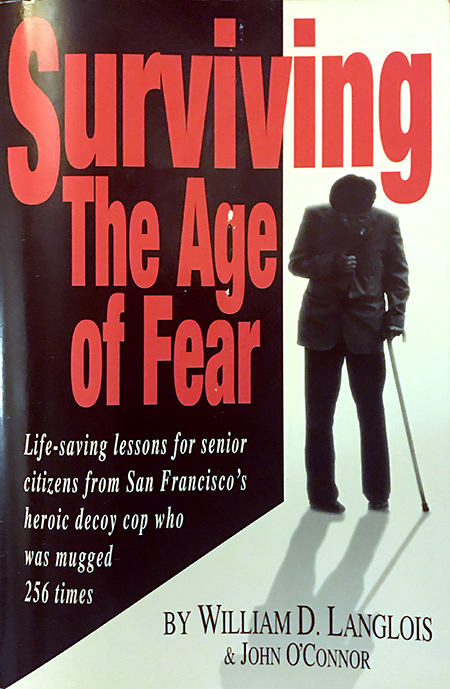

Surviving The Age of Fear

By William D. Langlois

Published Sept. 1, 1993 by WRS Group, Inc.

246 pages, paperback

ISBN: 978-1567960136

Reviewed by Gila Hayes

Last month’s lead interview with Ed Lovette included an excellent suggested reading list. One, Surviving The Age of Fear, was a book I’d read many years ago but was no longer on my bookshelves. Long out of print, copies still exist, although often priced prohibitively. I was very fortunate to find an affordable used copy online, but knowing readers may not have the same luck, I would like to share some notes from my rereading of a great story that contains many lessons.

The autobiography is written by William D. Langlois (1934-2001), a San Francisco, CA police officer famed for his undercover work posing as a fragile old man to catch violent robbers. As Lovette indicated in last month’s eJournal, Langlois’ exploration of what attracts criminals makes this story highly instructive. Even police officers rarely get to “watch a felony from the moment the idea pops into the head of the perpetrator to the instant it is actually committed,” Langlois wrote, but that experience taught the decoys and back up officers what factors balanced the risk-reward equation in a violent criminal’s mind.

The story takes place in the late 1980s and details three taskforces the San Francisco Police Department fielded to catch the men and women mugging the elderly. Criminals today may set the stage differently, but human unawareness remains unchanged, as does the way predators terrorize the frail. In Surviving The Age of Fear, security gates, doors and locks posed little impediment to those victimizing the elderly on Langlois’ beat. Attackers sometimes gained access and were waiting inside or pushed past the elderly as they unlocked a security gate or door. Actions play a bigger role than gates, fences or locks, so I began jotting down some notes to identify patterns in these crimes.

The story takes place in the late 1980s and details three taskforces the San Francisco Police Department fielded to catch the men and women mugging the elderly. Criminals today may set the stage differently, but human unawareness remains unchanged, as does the way predators terrorize the frail. In Surviving The Age of Fear, security gates, doors and locks posed little impediment to those victimizing the elderly on Langlois’ beat. Attackers sometimes gained access and were waiting inside or pushed past the elderly as they unlocked a security gate or door. Actions play a bigger role than gates, fences or locks, so I began jotting down some notes to identify patterns in these crimes.

In one episode, the female decoy officer portrayed an elderly lady going out for groceries and going home to her apartment. Upon returning, she sat down on the front porch steps to rifle through her purse as if searching for her keys. “Within minutes a 16-year-old male broke away from the crowd on the street and began watching her from a few feet away. When Leanna got up to open the security gate to the apartment building, the suspect followed, holding the gate open and slipping inside” where he mugged her, Langlois wrote.

The decoy officers tried a variety of costumes, make-up and accessories, but posture and mobility proved more important than white hair or wrinkles. Langlois would wear a built-up orthopedic shoe to create a bad limp or went for a walk outside wearing a single bedroom slipper. While walking through parks and other public areas, he could “feel the heat of inspection and I sensed that I had attracted the attention,” he wrote. A fellow robbery abatement team member commented that the criminals expected impaired hearing and vision in an 80-year-old man so while Langlois was alert to unusual interest, he was “careful not to put the guy off by glancing his way.”

Langlois identified and mimicked behavior to suggest he would be easy to rob. “I learned to look down, to keep my eyes on the ground, because most prospective victims are reluctant to make eye contact with their persecutors. In the urban landscape, the predators are the ones who have their heads up looking around.”

Another member of the robbery abatement team described seeing elderly citizens carrying their groceries home, “Trying to make it past these groups of young guys who stood on streets or in doorways and sized them up as they went by. Sometimes it was just a glance, a change of pace, but you knew what they were up to. These old folks…had pretty much given up hope. They were walking along with tunnel vision most of the time, thinking that if they kept their heads down and their eyes away from people, the bad guys would not see them and they would be able to make it home that day, wrapped in their own protective bubble, with their money or their groceries. It was disturbing to me to see this, because, of course, simply ignoring the threat was not enough to make it go away.”

Surviving The Age of Fear also gives insights into how predatory criminals hunt. I was surprised how many worked in teams, sometimes hooking up spontaneously before following Langlois back to the apartment from which decoy operations were run. One might trail him, while another went ahead. The one in the lead might stop to tie his shoe while assessing the victim. Relating one such incident, Langlois explained, “I crossed the street, moving away…forcing them to maneuver. Again, one of them ran ahead. He was hanging around, probably so he could pull me down behind two parked cars.” Eventually, the team would bracket the elderly man Langlois portrayed to herd him into a secluded location or rush him as he unlocked his door.

The criminals made a surprising amount of pre-attack contact to assess their victim’s level of awareness, including chatting with him or walking very close alongside. Langlois suggested they were assuring themselves the attack would prevail. As we’ve been taught by other experts, the predators are experts at their “jobs” and can be quite skilled. The 256 muggings Langlois endured demonstrated varying degrees of skill.

The robbery abatement team was eager to catch one violent mugger who hurt his victims so severely that several died and many were seriously injured. The team dubbed him “Whispers” because survivors reported that right before restraining and then attacking them, he quietly reassured them and urged them to be quiet.

Langlois wrote about arresting “Whispers” and his discussion of the robber’s skill is educational. He wrote that he passed a neatly dressed young man on the street. “When he glanced my way, I heard his intake of breath and his tennis shoes scrape on the sidewalk as he changed his course.” Langlois knew he had been targeted, but the robber concealed his intent so well that the backup team discounted him as a threat. When the man began to parallel Langlois from the other side of the street, they changed their minds, realizing that the suspect was very skilled.

Langlois unlocked and entered the apartment lobby, but unlike other attackers, the man only blocked the door open a fraction of an inch. Langlois stalled outside the apartment, fumbling with his keys until he finally heard the squeak of tennis shoes on the floor behind him. The suspect sat down on a bench in the lobby. Before Langlois finished closing the apartment door, the attacker was behind him, controlling his hands. He murmured reassurances to Langlois, but once the door was closed the suspect violently choked him and grabbed his wallet. The transformation was extreme.

During his arrest, the attacker resumed his genteel, respectful demeanor. “I remembered how he had reacted when he had the old man under his control…I felt if a person had really resisted him he wouldn’t stop until they were unconscious or dead,” Langlois wrote. “Surviving witnesses had told us this thief would assault and rob his victims and then meticulously clean the victim’s apartment, spending hours wiping and dusting everything until no trace of him was left behind.” The attacks in which elderly were quietly reassured then robbed stopped after the arrest although they were not able to link the attacker to the previous crimes.

Other muggers surveilled the decoy’s activities, identifying where he lived and studying the layout before attacking. Others chatted Langlois up while preparing their attack. One “tried to ingratiate himself with the old man first, saying his name was Bill and that he had just moved into the building. After a few minutes of this he decided the time was right, punched the old guy in the stomach, and reached for his wallet,” he wrote.

I was surprised by the distances from which the criminals would follow, hanging back, keeping Langlois in sight, sometimes from far down the block. Only when Langlois came to his building security gate would the criminals approach and separate if working as a team, look around quickly for witnesses, then push close to the decoy to get inside with him.

Those chapters make Surviving The Age of Fear a good police story, but also teach details about victim selection, the robbers’ hunting methods, and simple reactions that created such concern that most predators broke off and looked for easier victims. The final chapters of the book reflect Langlois’ deep concern for the elderly in America. Having outlived family, friends and associates, victims of many crimes he researched were elderly folks who were quite isolated. Many would have not have been harmed, he writes, had they only been walking to the corner grocery with another person.

I enjoyed rereading Surviving The Age of Fear and paid attention to descriptions of predators’ responses to eye contact and body language. I wish it was still in print and suggest members watch for copies in the used book stores or through online book sellers they patronize.

To read more of this month's journal, please click here.