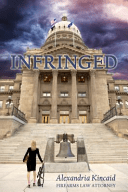

Infringed

Infringed

by Alexandria Kincaid

270 pages, 1st edition December 22, 2015

ISBN-10: 0996917535

270 pages, 6x9 Hardbound, Retail: $34.95 http://alexkincaid.com/index.php/orderbook/184-order-book

Reviewed by Gila Hayes

Gun laws are often confusing and sometimes contradictory, so we were pleased when attorney Alexandria Kincaid shared a copy of her new book Infringed to bring some clarity to this complex topic.

In 65 concise chapters, this Boise, Idaho attorney explains how laws are created, passed or nullified, how laws are interpreted, executive orders enacted, how juries work, appeals considered, what is actually Constitutionally protected, and much more, along with a number of definitions of terms for which we thought we knew the meaning, but to which the law actually applies its own sometimes counter-intuitive definitions.

The book’s instruction on how our courts operate is valuable, with civics so poorly taught these days. Chapter 3 of Infringed explains adjudication in court, appeals of court decisions, and how to read court decisions. Kincaid writes about the role of the jury at trial with similar clarity, and this is a good example of her book’s educational value. For example, while many think they can depend on a jury of people like themselves to clear them of spurious charges, the author suggests that such an outcome is not a sure bet.

Don’t confuse the evidence put in front of a jury with facts, she warns, adding, “Evidence is not fact…Evidence is what lawyers use to prove facts. The jury exists to hear the evidence presented to it by the parties or their lawyers during a trial and to make a decision base on the jurors’ collective interpretation of those facts and how the law should apply to them. The jury decides who is lying and who is not,” she explains.

This chapter goes on to explain rules of evidence, and the difference between a court deciding a question of law or a question of fact. “Legal questions are for judges to decide. The jury decides what happened and when. The judge will apply the law and make legal decisions, such as whether to allow the jury to hear certain evidence, which jury instructions to use, and often, which sentence is applicable.”

Some evidence will be withheld from the jury, Kincaid warns, “During a trial, juries get a brief introduction to the law and are expected to apply the law correctly in life and death situations.” Jury instructions are useful outside of a trial setting, as well, she explains, writing, “If you just read a statute, you will not necessarily know how your court interprets that statute when applying it to particular facts,” then offers examples to further clarify why we must understand more than just black letter law. As we lack room here to discuss all of the points Kincaid clarifies, the reader is encouraged to get this book and study it thoughtfully. Trial outcomes are not always just and fair, so the next chapter explains how trial outcomes are appealed, and a later chapter explains why appellate decisions in one court do not apply nationally.

The interplay between state law and Federal law is explained, as Kincaid reveals that you can be tried and punished more than once for the same act if convicted of breaking a state law then later found guilty of violating Federal law for the same act. In addition, cities and counties have their own laws, she continues in the next chapter, and many of these smaller entities are not as sensitive to Constitutional concerns. She gives an appreciative nod to the Second Amendment Foundation for their work challenging illegal restrictions.

Next, Kincaid embarks on a 17-chapter section to acquaint the reader with Federal gun laws, their enforcement and how you may become an “accidental felon.” This she illustrates with landmark cases infringing on individual rights. The complexity of these laws and the rulings that explain their application is clarified by short “What this means to you…” sentences highlighted on the pages containing the denser text.

She assigns the greatest numbers of unintentional felonies by gun owners to inadvertently violating either the National Firearms Act (NFA) or the Gun Control Act, both of which were ironically enacted in an attempt to protect America from organized crime. Tax stamps required for certain weapons, post-manufacturing add-ons that transform your legally-owned firearm into a regulated gun, and other details fill these pages.

Thirty some years after the NFA, the Gun Control Act piled more limits on gun possession, Kincaid continues. These restrictions apply not only to violent felons, but to people who accepted a deferred prosecution, are underage, were dishonorably discharged from the military, committed for mental health treatment, subject to a restraining order, convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence, and while the definition of those words seems clear, the application of the GCA has not been, she clarifies, illustrating one situation in which gun rights were taken away over the crime of rolling back vehicle odometers although the patchwork of drug laws is a more common reason folks lose gun rights.

Likewise, senior citizens receiving assistance with their day-to-day finances and other needs may find their gun rights stripped away. Kincaid comments that a gun trust can remove the government from that process because a strategy is already in place for the trust’s named agent or trustee to step in and manage things. This is a theme about which she has much to say in later chapters. Many reading Infringed will be shocked at how intrusive firearms laws are, affecting not only citizens with past brushes with the law, but large classes of citizens like the elderly and veterans.

Kincaid starts her analysis of lawful firearm possession and transport with a four-way chart defining the following factors: firearm, person, location and carrying ability to determine if there are Federal or state issues affecting the legality, or issues with the person in possession or if the firearm has been transferred legally.

Risk from the state-to-state patchwork of laws is highest for those who live close to a state border, and fail to realize that a gun that is legal in their state is not allowed just a few miles from home, she illustrates. Magazines that hold more than an arbitrary number of rounds are a common culprit, and in CT a number of semi-automatic rifles are no longer legal, she accounts. “State gun laws change so rapidly that any published compendium would be quickly outdated,” she warns.

Taking responsibility for securing your firearms is the message of the next chapter, as Kincaid outlines the liabilities gun owners face if their firearms fall into unauthorized hands. She relates the case of an Oregonian whose gun slipped from his holster and was left at a movie theater, concluding, “Never forget that your firearm is your responsibility. If other people are harmed by your negligence, you harm the entire gun owing community when the tragedy is publicized.”

Gun owners must honor private property rights of others, Kincaid next warns. Armed citizens who want to shop at anti-gun retail stores struggle with this concept, but she stresses that private property owners are allowed to regulate gun possession on private property. Federal facilities are gun free zones, and a surprising number of places fall into that category. One might not think that touring a cave in Yellowstone Park means entering a Federal facility, but it does, Kincaid illustrates. She emphasizes how gun free zones are anything but safe, asserting that, “states with the fewest gun free zones have the fewest gun-related killings, injuries and attacks.”

Infringed’s final section deals with using firearms for self defense, beginning with a firm endorsement of preparation and training to survive an attack and portray responsible firearms use in self defense to those investigating and possibly adjudicating the lawfulness of what you did. Prior preparation, in addition to training, includes attorney selection, a topic, naturally on which a practicing firearms attorney has strong beliefs. Additional chapters in this section draw the distinction between homicide and lawfully using deadly force, briefly explaining how the defense of self defense might be negated.

I would have enjoyed reading more of Kincaid’s thoughts on aftermath management, finding this chapter shorter than anticipated, although Infringed jumps back to aspects of post incident management in the books final chapters. First, she details how the criminal justice system gathers and processes the details that may result in criminal charges after a shooting, how those charges are filed or the facts presented to a grand jury, how grand juries function, and the timelines involved.

In the book’s next-to-the-last chapter Kincaid outlines interacting with law enforcement after self defense, recommending reporting the active dynamic of the crime against you that left you with no choice but to be killed or use deadly force in self defense, reporting the incident to 9-1-1, giving a brief statement to responding officers and knowing when to stop talking. Next she explains what happens after indictment, and briefly outlines the steps building up to trial. Negotiated pleas, acquittal or sentencing is sketched out in a few paragraphs.

Alexandria Kincaid has compiled a book of short, quick-to-read chapters that contain a lot of important information for armed citizens. I enjoyed it.

Click here to return to July 2016 Journal to read more.