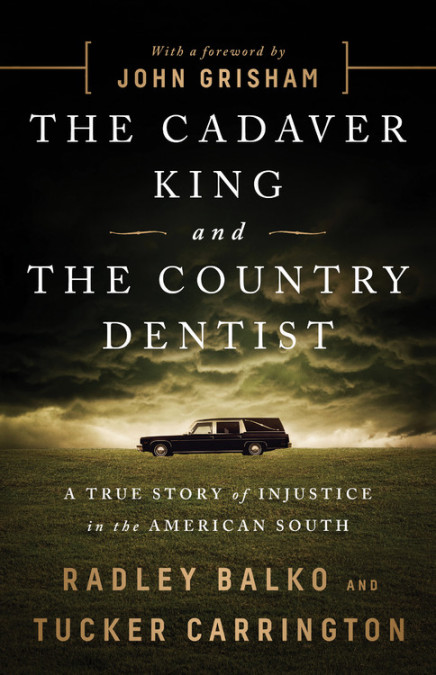

The Cadaver King and the Country Dentist

The Cadaver King and the Country Dentist

A True Story of Injustice in the American South

by Radley Balko and Tucker Carrington

ISBN-13: 9781610396912

Hardcover $28

ISBN-13: 9781610396929

eBook $12.99

Reviewed by Gila Hayes

The book I read in December is a report about two men who, co-author investigative journalist Radley Balko writes, “dominated the Mississippi death investigation system for 20 years.” You’ll note the word “report:” the word “story” suggests entertainment, and this book is serious coverage of a very real problem. It is also about two innocent men who were swept up in the 1990s campaigns for law and order, explains the co-author Tucker Carrington, head of the Innocence Project at the University of Mississippi School of Law.

I was interested in the book because the scope is larger than two bit players in the MS criminal justice system and their victims. While the ordeals of the innocent men are the stage for the bigger discussion, this book also spotlights the rush to convict, and how unquestioning adherence to law-and-order policies allows false accusations and convictions, while leaving murderers free to continue victimizing the population.

Although there are long chapters that don’t seem applicable to armed citizens’ concerns about the criminal justice system, The Cadaver King and the Country Dentist is a warning about expert witness testimony that should concern us. Juries need subject-matter experts to explain specialized knowledge that is so technical as to be beyond the grasp of most. Before letting expert opinions color a juror’s thinking, though, the court has to decide if a) their expertise is relevant to the issues on which the case turns, and b) if the science backing the expert opinion is reliable.

If an expert is going to explain an area of study, other requirements challenge the underlying science. Has it been tested and how often did the testing yield incorrect findings? Is the science subject to peer review and widely accepted in the scientific community? Was it applied using industry-accepted standards? I found this discussion interesting, not only in the context of the examples the book gives, but also thinking about the need to present expert witness opinions to explain use of force decisions.

The stage setting The Cadaver King involves badly flawed death investigations into the abductions and killings of two little girls in Mississippi, and the intransigence of county and state officials who refused to reconsider shoddy investigations and manufactured evidence even when shown the errors. In one case used to illustrate the issues, an initial sweep for suspects actually brought in the man who many long years later confessed to killing both toddlers. An incompetent investigator had already chosen a key suspect, so the killer remained free and did, indeed kill again before being caught and jailed.

After outlining the facts of two wrongful convictions due to unqualified expert opinions given in court by a dentist and physician, the authors outline the history of the position of coroner and its evolution from English tax collector into a patronage position in America in the 1920-30s. It indicts unqualified elected coroners rendering cause of death decisions on unscientific or flimsy evidence, and while the stories are set in a single state, there is little doubt that the problem exists all across the country.

Inexact scientific expertise comes in for equal criticism, not only autopsies performed by physicians with no forensics training, but analysis of bite marks, receives particularly harsh treatment. “Bite mark analysis, along with fields like tire tread analysis, ‘tool mark’ matching, blood spatter analysis, and even fingerprint analysis, all belong to a class of forensics called ‘pattern matching,’” they explain. “These fields are problematic because although they’re often presented to juries as scientific, they’re actually entirely subjective. Analysts essentially look at two samples, and determine, using their own judgment, whether or not they’re a ‘match.’ These analysts aren’t subject to peer review or blind testing. There’s no way to calculate error rates.”

By way of comparison, the authors note, “You’ll rarely find two experts who are diametrically opposed about a victim’s blood type or how many DNA markers match the defendant. That’s because those are questions of science. In pattern matching, expert witnesses regularly come to opposing conclusions. Juries are simply asked to side with the analyst they find more convincing.”

If pure science was the only factor involved, we’d be on surer ground. Of course, humans have to apply the science, and when investigating deaths, that starts with law enforcement and coroners or medical examiners. Balko and Carrington explain, “Medical examiners are supposed to be impartial finders of fact. But the incentives built into the system are clear. After a suspicious death, the coroner, district attorney, or police official takes the body to a medical examiner for autopsy. In most cases, they then tell the medical examiner what they thought happened. The medical examiner who returns with opinions that back up their hunch earns favor and gets more referrals. The medical examiner who says, ‘No, that isn’t what happened,’ or – the more likely scenario – ‘There just isn’t enough conclusive evidence for me to say that this is what happened’ makes the sheriff’s or prosecutor’s job more difficult, and perhaps makes them think twice before using the same doctor the next time. There needn’t even be any intent to deceive or distort findings. It’s human nature...”

As early as 1923 the courts began to weigh the difficulty of determining guilt through scientific analysis of evidence, the authors point out early in the book. The 1923 case Frye v. United States entailed the practice of polygraphy. “In considering whether to allow the expert opinion, the court ruled that in order for scientific evidence to be admissible it must have ‘gained general acceptance in the particular field in which it belongs.’

“It made judges the gatekeepers of what expertise would be allowed into court. The problem is that judges are trained in legal analysis, not scientific inquiry,” the authors explain, noting that, nonetheless, Frye remained the standard through the late 1970s.

Quoting an evidence expert and university professor, the book suggests, “Most of the time when doing one of these analyses, the only thing a judge will ask is, ‘Have other courts allowed this?’ says Arizona State University law professor and evidence expert Michael Saks. ‘If the answer is yes, then they’ll figure out a way to let it in. Or they’ll decide that if the government is paying a person to do this analysis, it must be legitimate. That’s a far cry from an analysis of its scientific merit. But it doesn’t seem to matter.’”

You’d like to think we had better standards today! The authors aren’t so sure. “For seventy years after the Frye decision – the case that set the standard for distinguishing good expert testimony from bad – the US Supreme Court steered clear of establishing any rules for the use of science in the courtroom. In 1993, the court finally addressed the issue in a series of rulings known as the Daubert decisions. The main decision came in Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc.” Here, the Supreme Court “loosened the standard for the admission of scientific and other technical evidence, but also institutionalized the judge’s role as the gatekeeper of such evidence.” Unfortunately, the authors opine, for that to work, judges would need “some minimum competency in scientific literacy,” which, of course, the criminal justice system can’t realistically assure.

Although The Cadaver King and the Country Dentist concludes with the end of the guilty physician’s and dentist’s careers and the release of the two innocent men, the reader is left with concerns about errors and prejudices in the criminal justice system that extend far beyond that story. Books that make us question the status quo are good, and while this book is different than our usual review material, I thought it was worth the time it took to read it.

To read more of this month's journal, please click here.