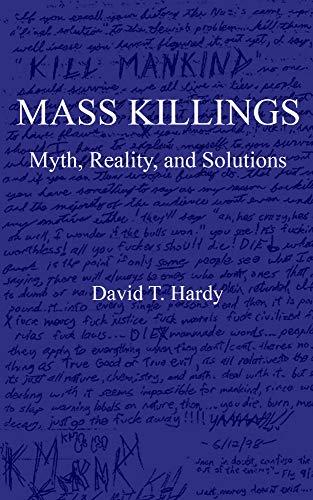

Mass Killings: Myth, Reality, and Solutions

by David T. Hardy

68-page paperback

ISBN-13: 978-1718142244

44 page eBook sold at Amazon Digital Services LLC

Reviewed by Gila Hayes

I have been a regular reader of David Hardy’s Of Arms and the Law blog for many years, so recently when I stumbled across his analysis Mass Killings: Myth, Reality, and Solutions, I added it to my e-book library immediately. I’ve always liked the plain-spoken Hardy’s blog commentaries, although he is more rightly famous for his work as an attorney and legal scholar.

In his introduction, Hardy writes that reports on mass killer attacks range from serious scientific studies to news soundbites. He draws lessons from 21 mass killer attacks between 1966 to 2018 in “an attempt to bridge the gap by condensing and organizing the work that has been done on the subject by criminologists, psychologists, psychiatrists, and others.”

In his introduction, Hardy writes that reports on mass killer attacks range from serious scientific studies to news soundbites. He draws lessons from 21 mass killer attacks between 1966 to 2018 in “an attempt to bridge the gap by condensing and organizing the work that has been done on the subject by criminologists, psychologists, psychiatrists, and others.”

Myths and outright lies he debunks include the claim that mass killer attacks are a uniquely American problem tied to firearms. He points out, “The record death toll from a mass shooting came in Norway, in 2011: 67 deaths. The record death toll from a mass killing of any type came in China, in 2001; the killer used bombs to take 108 lives. In 1982 a berserk South Korean policeman killed 56 (the same number that died in our worst shooting, in Las Vegas), in 2007 two Ukrainians killed 25 with a hammer and a pipe, in 1986 a Columbian used a six-shot revolver to kill 29 in a Bogota restaurant...(Neither America’s worst mass slaying or its worst school slaying were shootings. The man who torched the Happy Land nightclub in 1990 killed 87; the one who blew up the Bath, Michigan schoolhouse in 1927 killed 44).”

Is access to firearms the reason behind mass killings? No, Hardy points out, illustrating his conclusion by citing the multiple deaths from knife attacks in China, bombings in various nations, and mass killings by terrorists driving automobiles.

Are mass shootings on the rise? Hardy writes that they are not. The media creates that impression by manipulating the data and the definitions of mass killings to include suicides, gang violence, shootings over drug deals and other crimes unrelated to a mass killer’s desire for notoriety. He also addresses the mistaken idea that spree killers “snap” and kill without warning, noting long periods of preparation, methodically developed plans, and acquiring and stockpiling weapons and other supplies that investigators turn up in the aftermath.

Are mass killers pushed into madness by having been bullied? Not so, Hardy says, explaining that normal folks grasp at any explanation, including this popular theme. His research suggests that the mistaken notion about bullying was launched at Columbine. He comments, “The sound bite coverage…focused on [the killers] as innocent victims of a toxic teen culture in which they were persistently harassed. This one-sided view has become fixed in many people’s minds…”

In reality, Hardy observes, mass killers are narcissistic, are themselves frequently bullies, and often are psychopathic or sadistic. “All these are classes of people accustomed to inflicting verbal and emotional abuse to get what they want from others...When the killers are loners, it’s not usually a cause of their condition, but its effect.” He later adds, “Apart from the psychotic ones...virtually all mass killers are extreme cases of narcissistic personality disorder. They have grandiose views of themselves and of their importance, and expect everyone to share this self-appraisal.”

Hardy continues, “Narcissism and psychopathy make a dangerous combination.” He calls, “A conscienceless person with no regard for laws or their fellow humans, coupled with a burning need for recognition in the form of fame or infamy, and anger that this recognition, this entitlement, has been denied him,” the “recipe for creating a mass killer.” The characteristic of sadism is another common factor shared by mass killers, he adds. Others have shown symptoms of depression, he acknowledges, while some post-incident manifestos reveal seriously disordered thinking suggesting schizophrenia, delusional thinking, and in one example a psychotic break, although he adds that these mental disorders are less to blame than narcissism, psychopathy and sadism.

In chapter 3, Hardy spotlights the news media’s fascination with mass shootings and how it serves mass killers. The Virginia Tech killer sent NBC news pictures, videos and long, rambling writings; reporters fought to provide the most dramatic details about the Columbine killers, a campaign that persisted for most of the year after the murders and included two Time magazine covers featuring the murderers’ faces. He cites several interrupted attacks in which investigators found detailed plans specifically patterned on Columbine, showing how the next crop of psychopaths drew on the frenzied reporting, much of which simply was not true like the reporter who gushed that Columbine students found the “sadistic psychopath and his sidekick who dreamed of killing hundreds of children” sweet or adorable boys, highly intelligent, and loyal to friends.

Hardy argues that news media should deny mass killers the celebrity they seek by refusing to name them or run their photo. Experts suggest minimizing “images of terrified or grieving survivors,” to avoid portraying them as powerful to would-be copycats, he adds. Refuse to publish their manifestos or videotapes and never blame the murders on persecution the killer endured. Statistics prove that “publicity given mass killers generates more mass killings,” in that they “tend to come in clusters following a heavily-publicized one,” he adds. At the book’s end, he recommends making mass killers nameless and faceless, as the cure with the greatest potential to prevent others from following suit.

Hardy may be bucking a trend when he advises improving the mental health system as part of the solution. He suggests that in most cases, involuntary commitment and treatment is needed, although that is difficult to achieve in today’s society. The man who shot Gabrielle Giffords was “known to be insane and dangerous,” but no one called authorities to intervene. He encourages increased public willingness to report warning signs by killers who post their ideas on social media, are known to be collecting supplies for an attack, or message their friends about what they’re going to do.

Gun control, waiting periods, background checks, banning private party gun sales, bans on military-style guns, magazine capacity limits and other popularly acclaimed measures would not have prevented the mass killings in past years. Hardy instead recommends increased security measures, noting that schools have benefitted from having school resource or security officers, and he extends that concept to include volunteer armed teachers. “We know that mass shooters consider security in choosing a target,” he writes, noting that the Aurora theater killer wrote that he thought about airports for his killing spree, but ruled it out because of security. The Orlando nightclub shooter abandoned one location after seeing security officers there and focused his attack instead on the Pulse nightclub. Create uncertainty in the would-be shooter’s mind about success, Hardy recommends, asking rhetorically, “What does such a narcissist dread most? Failure. Failure means he dies and is forgotten.”

Hardy urges readers not to view spree killer threats as unsurmountable. “There are things that we can do to reduce mass and school killings. We can moderate the publicity that comprises their motivation. We can provide better, much better, mental health care and reduce the legal barriers to providing it to those who need it but will not seek it. We can harden the schools. The hardening does not need to be perfect; just raising the risk of failure will deter school killers,” he urges.

Hardy’s book concludes with a list of articles and books by a variety of experts and a substantial set of footnotes to support the assertions in this concise little book. The 24-hour news cycle spouts so much fear mongering that it is easy to think change is impossible. If David Hardy’s book has one key message, it is this: there are solutions to spree killer attacks. Several, in fact. I was encouraged and inspired by his book.

To read more of this month's journal, please click here.