Recently, I received the following e-mail:

Recently, I received the following e-mail:

Good day. I read an article written by Mr. Hayes titled ‘Call the Experts’ in Gun Digest. He encouraged people to inquire about becoming a court recognized expert in self-defense cases. Will you please forward my inquiry to him as to how best to proceed on this matter? Thank you for your consideration.

Respectfully,

[Name Withheld For Privacy]

I responded that it was a great question, requiring an answer that is way too extensive for e-mail. I promised to instead write an article for the Network eJournal, as others might be interested, too.

I first learned about testifying in court as an expert witness back in 1990, when I attended Massad Ayoob’s Lethal Force Institute. During the classroom presentation, he spoke about several instances where he testified in court and saved the bacon for the armed citizen or police officer. I remember thinking, I would really like to help people who are wrongfully accused of a crime after an act of self defense.

It turns out there were not that many cases in the greater Seattle area, and besides, I was spending all my time trying to develop my shooting instruction business, so I didn’t get my first case until 1992. One day, I got a call from the Seattle Public Defender’s Office. The attorney, who found me in the Yellow Pages, asked if I could help figure out the firearms evidence in a case. I told her I could try, and so she sent me the discovery, which included the police reports, autopsy report, shooting incident photos and the defendant’s statement to police.

The defendant, a young teenager, told the police that while watching TV, he was fiddling around with a Smith and Wesson Model 37 revolver that his mother had bought because she worked nights and didn’t want him and his sister at home without some sort of protection. His sister walked in front of the TV, the gun went off, and his older sister was shot. She died. The police arrested him for first degree manslaughter.

There were two pieces of evidence that tended to support his story. The first was a jagged wound on the side of his left thumb, and the second was light primer strikes on a couple of the unfired .38 caliber cartridges. Due to the primer strikes, I figured that he was cocking the gun and letting the hammer off, and a couple times the hammer slipped and hit the primer, but not hard enough to fire it. This would tend to support that he was just fiddling around with the gun.

As far as the jagged cut on his thumb, the only thing I could figure was that he was loosely holding the gun, and the gun had been cocked and the hammer slipped, discharging a round at the same time the sister walked in front of the TV. But how could I establish evidence to support my conclusions?

It so happened that I owned a Smith & Wesson Model 37, so off I went to the range with a box of .38s, the revolver and a pair of leather gloves, to attempt to re-create the shooting mishap. I sat on the ground with the gun in my lap and fiddled with the gun (always pointed in a safe direction). I could cause the light primer strikes by cocking the gun with my finger on the trigger and releasing the hammer by pulling the trigger. The gun would not fire but would result in firing pin strikes on the primers. So much for the first mystery.

With gloves on, I then did the same thing, holding the gun loosely and cocking the gun fully, and letting the hammer fall with my finger on the trigger. The result? The gun, a lightweight snub-nosed revolver, recoiled so violently that the sharp edge of the hammer caused a mark on the leather glove, the same spot as the wound on the defendant. Mystery #2 solved.

When it was time to testify in court, I had a secret weapon: a video tape of the re-creation. The judge saw the video, listened to my explanation, and the defense rested its case. The result? In less than 15 minutes the kid was found not guilty, with the judge explaining that the event was likely an accident, thus there was no criminal intent. Ever since that case, I try to video all the testing I do for cases.

After the Smith & Wesson Model 37 case, I became the go-to guy for the Seattle public defender’s office when they had cases in which they did not understand the firearms or ballistic issues. I took pretty much all of the cases they asked me to, not because they involved self defense, but because the court needs to understand the firearms/ballistic evidence. Furthermore, in the event the defendant is being overcharged (for example, murder instead of manslaughter) I feel compelled to make sure the correct charges stick. In many cases, the murder charge may be replaced with manslaughter and a plea deal struck.

You are likely wondering why I would work on cases where the defendant was clearly guilty of a crime. It is because the defendants were not guilty of the crimes with which they were charged, and I abhor the practice of prosecutors overcharging. Taking those cases also gave me experience so when I did have a case where the defendant was truly innocent, I could do a better job as an expert. The Model 37 case illustrates the type of case where a gun-savvy individual, such as an instructor or someone who works in the firearms industry, could become an expert witness for court.

There are other areas of expertise outside of “firearms expert” to explore, but before we do that, let’s take a quick look at why an individual can give expert testimony in a criminal or civil case. The Federal Rules of Evidence include specifics about testimony by experts. See https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/fre/rule_702 .

Rule 702. Testimony by Expert Witnesses

A witness who is qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education may testify in the form of an opinion or otherwise if:

(a) the expert’s scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will help the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue;

(b) the testimony is based on sufficient facts or data;

(c) the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods; and

(d) the expert has reliably applied the principles and methods to the facts of the case.

Most, if not all of the states, follow the Federal Rules of Evidence. This opens the door for a firearms instructor to come into court and give testimony. There are restrictions, typically defined by case law in each jurisdiction. If you are interested, delve into the case law of your state to look at the individual issues you may face. Now, let’s get back to the individual areas of expertise about which you may find yourself testifying in court.

Being a Ballistics Expert

Firearms instructors are typically experts in ballistics, especially if they are reloaders. A case may have a need for a ballistics expert, as was true in the following:

One case involved a drive-by shooting. The defendant shot back against the guys on the street who were shooting at him. The defendant was shooting a Beretta 9mm, and the deceased, one of the guys on the street, died from a 9mm gunshot wound to the back.

After looking at the evidence, I noted in the crime lab report that the bullet was a 90 grain 9mm. Does that suggest anything to you? It told me that the defendant did not shoot the deceased. Why? Because the 90 grain 9mm is typically loaded in .380 caliber, not 9mm Parabellum. I told the defense attorney to have the police go out and canvas the area better, looking for a .380. Sure enough, the cops found a Walther .380 under some bushes at the shooting scene. Case dismissed.

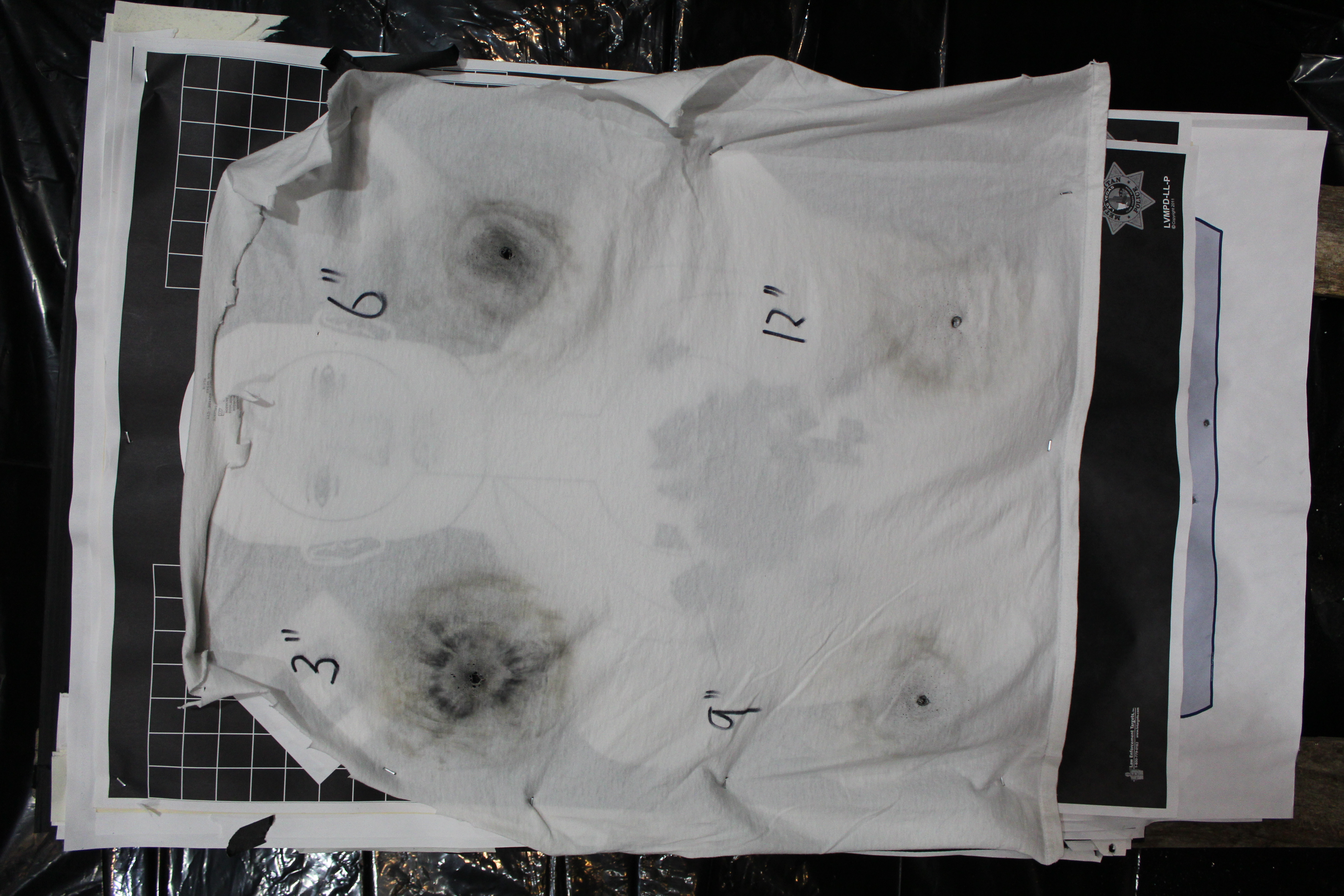

Another situation which requires ballistic expertise is determining how close the shooter was to the deceased by conducting stippling testing. The test can be useful if you have observed stippling and have the gun and ammo from the shooting with which to do testing. I have been able to get away with an exemplar firearm, but you will almost certainly need the same type of ammo for the testing. You can refer to textbooks on shooting incident reconstruction (more about this later) to learn how stippling testing is conducted. I have worked on cases where I was tasked to ascertain the positions of the deceased and the shooter, based on the trajectories of the bullets and bullet strikes. This is pretty common.

Photo, right: Gunshot residue and stippling test to determine distance of muzzle to shooting victim.

I have worked on lots of cases where shots were fired at vehicles while moving. In another case, I wrote an expert report regarding the killing of a mother cougar, when it was coming at a bear hunter. He fired in self defense, and I was able to show that the wound was consistent with an attacking cougar, not one that was running away. That case was dismissed before trial.

Expertise in “Dynamics of Violent Encounters”

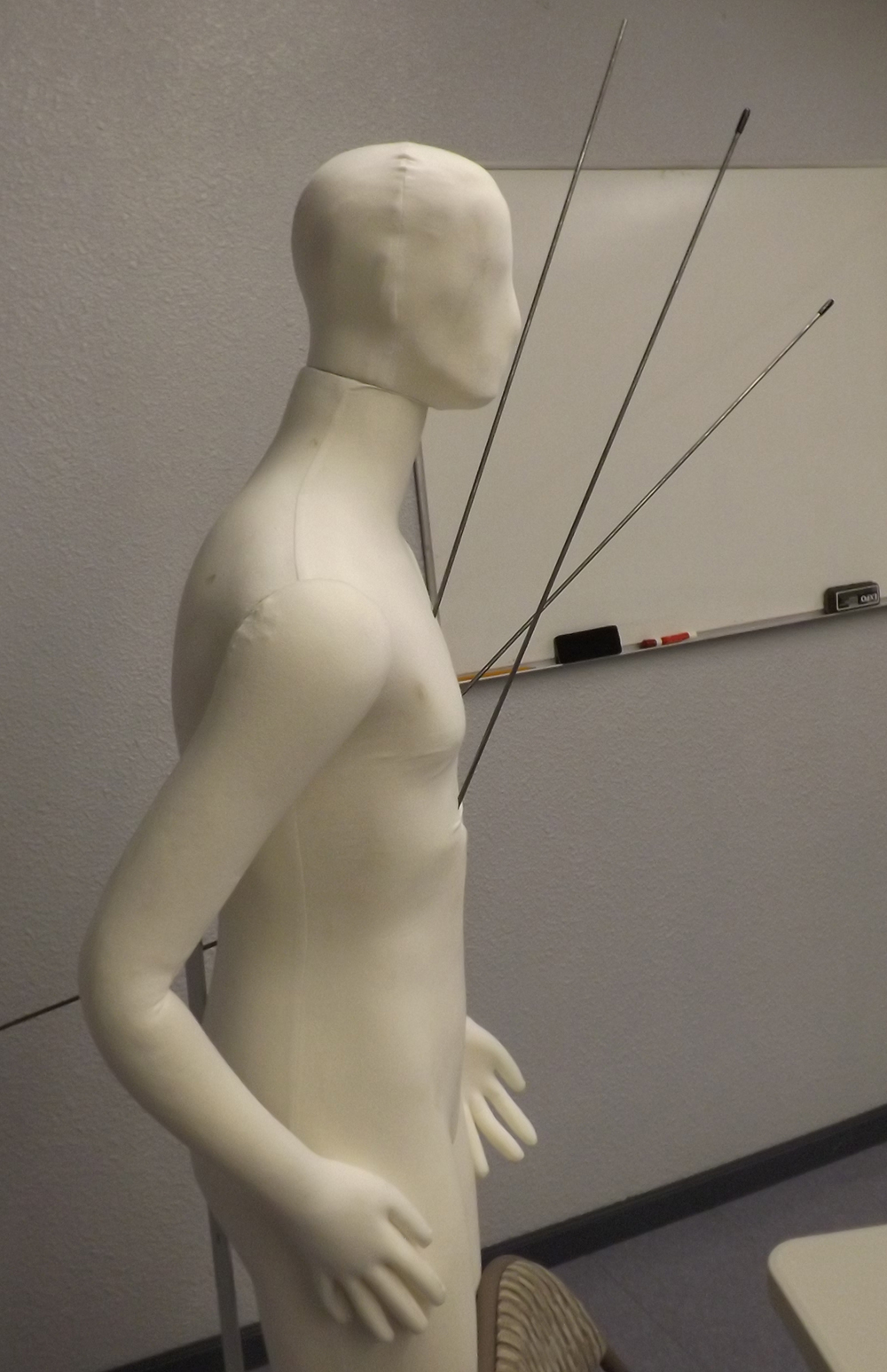

What were the persons involved in the event doing right before, during and after the shooting? This question typically arises in cases where a person was shot in the back, although the shooter claims he only shot while the deceased was facing him. In one such case, the defendant was being threatened and he shot in self defense. One of the bullets struck the deceased in the back, and that was enough for the police and prosecutor to charge the defendant with first degree murder. It fell to me, as the expert, to explain how that could have happened. The whole story can be read in this three-part story in a past edition of this journal starting at https://armedcitizensnetwork.org/anatomy-of-a-self-defense-shooting . I have worked on several other similar cases. This is the field of dynamics of violent encounters, an area of expertise one can read up on and get training in. For more information on becoming an expert in dynamics of violent encounters, see https://armedcitizensnetwork.org/the-science-of-self-defense .

Use of Force Expert

Another area of expertise is in use of force. Most of the time, this expert testifies at police excessive force trials, but the field of study is applicable to an armed citizen’s trial, too. The use of force expert cannot testify whether he or she believes the defendant is innocent or guilty, but a skilled attorney can make use of the “hypothetical person” to get the point across to the jury. For more information about this type of expert, see https://armedcitizensnetwork.org/disparity-of-force .

That list pretty much sums up the areas where an armed citizen who is qualified as an expert can testify at trial.

In April 2017, the Network did an interview with noted expert Manny Kapelsohn (also a Network Advisory Board member) regarding the role of expert witnesses. He addressed the subject of how to become an expert so well, that I certainly could not do it better. Read that interview at https://armedcitizensnetwork.org/the-role-of-the-expert-witness before you read further in this article. Please also read the second part of the interview with Kapelsohn https://armedcitizensnetwork.org/the-role-of-the-expert-witness-part-2 then I will pick up the topic from there.

How to Get Started

You are likely wondering how to break into the field of expert witnessing, and what is required if you do get a case. First, if you are a firearms instructor, you might simply get a call out of the blue based on your business, and you take it from there, but that is probably not the quickest way to get started. One thing you can do is advertise with your local bar association, or separately to the local criminal defense bar. Get some phone numbers, make a few phone calls, and talk with the receptionists, explaining that you want to start serving as an expert witness, and you would like to advertise your services. If this sounds daunting, you are probably not a good candidate for this field, because there is a huge amount of stress when testifying in court, knowing that someone’s freedom rests upon how you do. If you can’t handle the stress of a few cold calls, then you will likely fall apart under cross examination.

You can also follow criminal cases in the newspaper or on-line news service, and if a case strikes you as one where you might be able to help out, call the attorney the news source identifies. Offer to take a look at the discovery for no fee. There is nothing for him to lose and all you will lose is a little time. Let him know you want to break into the field and need some experience. You might even volunteer to work on the case for free, just to get the experience. (I did this in the Ronda Reynolds case, discussed later).

Another thing you will need is a Curriculum Vitae. Huh? A CV is a fancy way of saying “résumé,” but make it clear you are not looking for a job. Instead, the CV is a one to several page document that outlines your qualifications for the court. Remember the requirement to be accepted by the court as an expert? This is where you tell the court, and the attorneys involved in the case, who you are and what experience, education, and training qualifies you as an expert. Now, whatever you do, do not embellish on this CV. Don’t round up dates or exaggerate a qualification. If this is a high-profile case, with lots of money on the line (remember George Zimmerman?) the other side might just send a squad of investigators out to check out every detail on that CV, intent upon discrediting you on the witness stand.

The Nuts and Bolts

If you take a case, you will be required to do the following:

First, do a complete review of discovery (the evidence of the case). Even if you are being asked only about a specific aspect the case, you want to be able to testify that you reviewed ALL of the discovery. If not, you can be strongly criticized during your testimony. I take a notepad (or my computer) and make a note of every document I review, all the pictures I see, and every interview I listen to.

I also use this document to keep track of the time I spend, since you will generally charge by the hour. Alternatively, the attorney may ask you to take the case on a flat fee, paid up-front. If you accept this, do yourself a favor and don’t cash the check until you are through reviewing the discovery. You may find out the case is nothing with which you want to be associated.

After reviewing discovery, you will want to discuss the case with the attorney. Do this in person or over the phone, not over e-mail. E-mail is discoverable, especially in civil cases. At this time, depending on what your review indicates, the decision is made if you are going to continue working on the case. If I am dismissed from the case or decide to withdraw, I will send the uncashed check back to the attorney, but that is just the way I operate. The few hours I spent are not that important to me, I certainly learned something new, and the money isn’t that critical to my survival. Your situation may be different, so make sure the attorney understands that you are billing for review of all the discovery, even if you do not work further on the case.

Speaking of Billing…

There are several ways to get paid. One is the flat fee, which we have already discussed. The other is a retainer, and you work and bill against a retainer that is based on an estimate of how many hours you expect to spend. I usually do this, taking a retainer up to being finished with my report, and if it goes to court, then I bill for the time for court.

The last method is usually reserved by public defender cases, in which you are going to be paid by the county or state. If this is the case, you bill after the court case is resolved, be that by plea or a trial. You will want to get an authorization for the payment from the judge (the attorney you are working for handles this). After getting this authorization signed, you are free to work on the case with an assurance you will get paid, up to the limit imposed by the judge. This can be revised upward, if necessary. One other thing, some attorneys will take a short cut and just have the client pay you directly instead of depositing the client’s money into their trust fund and then writing you a check out of the trust fund. Don’t fall for it. Accepting money directly from the client opens you up to the court room attack, “Isn’t it true, Mr. Hayes, that the defendant is paying you to testify for him here today?”

The Expert Report

Now, you will need to write a report for the attorney for whom you are working. This report can become evidence for the jury to review (along with your CV). Make sure everything is grammatically correct, along with spelling and sentence construction. This can take several hours.

At this point, you will be waiting to see if the case goes to trial. In my experience, about two-thirds of the time the case is resolved and that ends your involvement, but you are not loafing during this time. You will want to write out questions you want the attorney to ask you in court to qualify as an expert. I do this every time because I want the attorney to ask me the right questions. Every time I have done this, I’ve been accepted as an expert, but in some cases where I did not do this, I was denied being able to testify. Not being allowed to testify hurts the pride, but the blame is on the attorney, not you.

I also draw up my direct testimony questions and give this to the attorney before trial. Most times the attorney will be grateful for this help, and I tell them that they are free to use the questions or not, but if they don’t and your client loses, it’s not my fault.

I started this procedure after I was hired on a felon in possession of a firearm case. The defendant had slipped a .22 caliber cartridge in the hole in a bicycle handlebar stem bolt which acted as a chamber and barrel. The state declared the bicycle stem bolt and hammer a firearm. I had no affection for the defendant, but it was the legal precedent of calling a bicycle part a gun that made me decide to take the case. The attorney did a dismal direct examination of me, and after the case was over and his client lost, the attorney blamed the loss on my lack of succinct testimony. After that experience, I always draw up direct examination questions.

Supplementing Your Report

In most cases you will likely need to do some testing, either stippling testing, case ejection testing, or some type of ballistic testing. I am firmly convinced that if the testing lends itself to videography, you should record video of the tests. If the testing does not lend itself to video, then by all means photograph the results. Even if the videos or photographs are not used in court, having them will help protect your credibility if you are accused of faking the results. It happens.

Other Cases

I have worked on several cases where the client was the parent or parents of someone who committed suicide or at least that is what the police were claiming. After all, it is much easier to investigate a suicide. In all but one of the cases, the evidence pointed to suicide, granting the parents some closure. One case was an anomaly, both the coroner and sheriff’s department were calling the death of Ronda Reynolds a suicide, but the ballistic evidence said otherwise. Eventually, the incumbent coroner lost his job over the case. After both a judicial review of the case in which a jury looked at the evidence presented, and a coroner’s inquest, two juries decided she was murdered. The case was the subject of a true crime novel In The Still of the Night, written by late true crime author Ann Rule (available on Amazon).

Testifying at Trial

Wear a nice suit. If you don’t have one or are not willing to buy one, don’t become an expert witness. Clean up before trial. There are many fine firearms instructors who have long, shabby beards and a plethora of tattoos. Obviously, tats can be covered, unless they are on the neck, face, or hands. Tats can turn off members of a jury and that would be bad for your client. You don’t need to shave your facial hair, but certainly trim it. If I was hiring an expert, unless the jury was a group of Hells Angels, I would not hire the person if there were visible tattoos.

When testifying, don’t simply answer the attorneys’ questions, when an explanation is in order. The defense attorney should be wise enough to frame the questions like this, “Mr. Hayes, could you explain to the jury how you came to your ultimate opinion in this case?” This would allow the expert to become a teacher in the eyes of the jury, explaining the scientific processes involved with your analysis, and how you applied this knowledge to form an expert opinion. In police work, cops are taught to address the jury when answering the questions, but it becomes comical when they answer yes or no questions by turning to the jury each time they say “yes” or “no.” Make sure this does not happen, turning you into a bobblehead. If an attorney asks a yes or no question, just answer to the attorney. If they ask “please explain” that is the time to turn to the jury.

Be sure to give the defense attorney time to object to a question before answering. A question may be cause for an objection, and you do not want to be giving the answer while the defense attorney is objecting.

If you don’t know, you don’t know. Do not be afraid to say you don’t know, or if you don’t understand the question, don’t be afraid to ask for a clarification. The jury probably doesn’t understand the question either.

Plain language is best. Speak to the least educated person on the jury, not the most educated. There are times where you must use a technical phrase, but before you do so, or immediately after, explain the technical phrase to the jury using plain language.

Training to Become an Expert

There are many books available to help educate you about serving as an expert witness. Just search the internet. Start with the term “shooting incident reconstruction,” followed up by “crime scene reconstruction.” As far as the latter though, avoid using that term when testifying or in your report, because doing so intimates that the client committed a crime. Sure, there was a crime, but the crime was the act the individual who got shot was doing, not what your client did.

You can attend live training to increase your expertise. Force Science would be a good starting point, along with Deadly Force Instructor from the Massad Ayoob Group, a class I helped design and teach. Learn about it at https://massadayoobgroup.com/deadly-force-instructor-class/ . The more classes you can take, the better.

Summary

I hope this answers the original question in sufficient detail that the reader can decide if becoming an expert witness is something to consider doing. The world of armed citizenry needs expert witnesses who can go to court and educate the court about what we face when deciding to shoot or not.

__________

Network President Marty Hayes is a familiar voice to most Network members. He brings 30 years experience as a professional firearms instructor, 30 years of law enforcement association and his knowledge of the legal profession both as an expert witness and his legal education to the leadership of the Network. See his bio at https://armedcitizensnetwork.org/learn/network-leadership for more details.